There are few topics I find more fascinating than the rise of Spiritualism in the early 20th century — and Houdini’s determination to rebuke it. Add to it the real life friendship — and falling out — between the master of magic and the creator of Sherlock Holmes, and it’s almost too good to be true.

There are few topics I find more fascinating than the rise of Spiritualism in the early 20th century — and Houdini’s determination to rebuke it. Add to it the real life friendship — and falling out — between the master of magic and the creator of Sherlock Holmes, and it’s almost too good to be true.

The noble dead, the Lost Generation as Gertrude Stein called them. An entire swath of the population was killed in WWI, followed by the deadly Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918. Death was everywhere. And in the midst of all the mourning, some wise people sought hope. Theosophists and Spiritualists sought to prove that there was merely a thin veil between this world and the next, and those who were willing to listen could speak to the spirits from beyond.

A great number of respectable people believed. Even more wanted to believe. Harry Houdini, the most cunning and creative illusionist and escape artist ever known, insisted these seances were nothing more than a parlor trick. Some were better than others, but a trick that he could reproduce himself. As he learned more about the numbers of people being fleeced by so-called mediums, he launched an all out war against the spiritism movement.

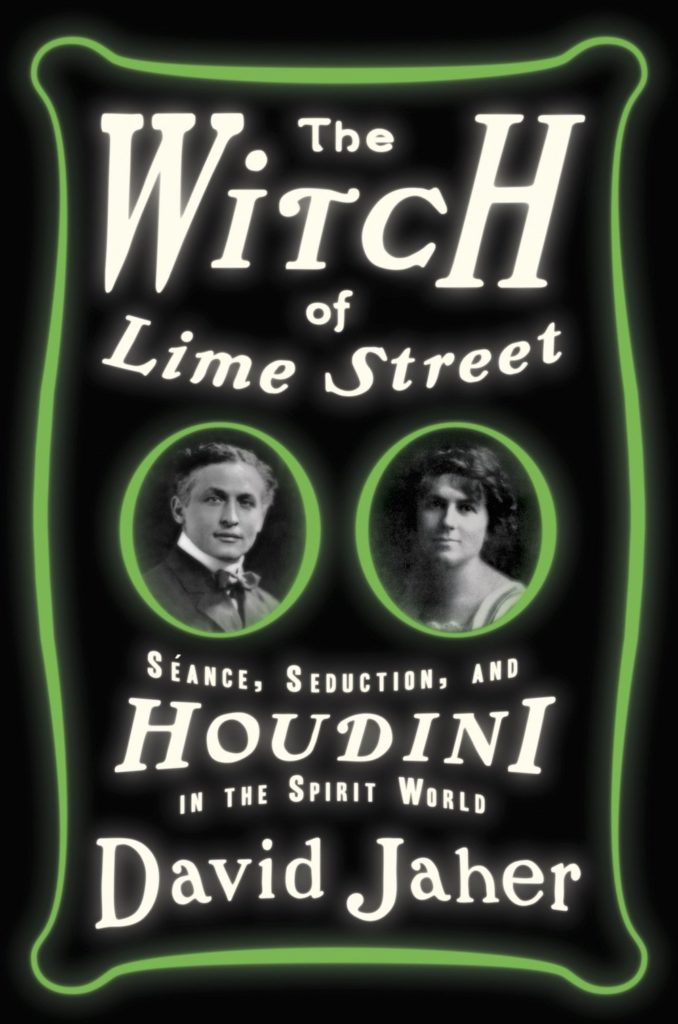

Jaher focuses on one particular specimen of interest. Margery, the “Witch of Lime Street” became the subject of months of tests and study by a team brought together by Scientific American. In order to maintain anonymity, they agreed to refer to Mrs. Mina Crandon with a fake name during the investigation. Mina was the very respectable wife of a very respectable doctor and they lived in a very respectable neighborhood in Boston.

As Malcolm Bird stood on the outside of the circle, watching the medium seated within her black, open-faced cabinet, he sensed wariness from the group that still blamed him for the setback the previous November — when a hostile force was drawn to the seance room. Was that to be the case once again? Bird wondered. Clearly Margery could dazzle her friends, even those scientists, and confound a few university psychologists; she could impress a few, mostly geriatric, European experts; but when it came to sittings with a representative of the Scientific American, would she once again conduct blank seances and blame it on superstitious devilry? ~Pg. 196

Mina was subjected to dozens of tests and restraints over the course of months. One of her most frequent visitors was Harry Houdini, who, it seems, wanted the Other Side to be real but had yet to be convinced of it. The two had a mutual admiration for a long time but he eventually grew weary of her sideshow tactics and she was irritated by his refusal to believe. Their relationship deteriorated, as did his friendship with Doyle. It seemed the more he proved, the less the believers wanted to hear.

- Jaher sets up a fantastic showdown, with details of place and person. Frustratingly, the book never quite culminates in it. Just as the explosion should happen, the firework instead fizzles and stutters off in a half-planned direction. Jaher is hampered somewhat by the true events. He cannot simply create a scene that didn’t happen. He could, however, have anchored the interactions between Margery and Houdini, especially their final one. Because of the book’s structure, the reader is led to believe there will be another encounter and some sort of resolution will be reached. Instead, it retreats into interesting tidbits best left for a true epilogue.

The research surrounding this book is fantastic and the energy is undeniable. Jaher is clearly intrigued by the topic and eager to share it with his readers. It’s only weakness is a lack of some sort of conclusion that lives up to the rest of the story.

Many thanks to Crown Publishing for the review copy.

(P.S. Just for fun — the border on the book cover glows in the dark.)

[xyz-ihs snippet=”4-and-half-stars”]

Hardcover: 448 pages

Publisher: Crown; 1st edition (October 6, 2015)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0307451062

ISBN-13: 978-0307451064

Product Dimensions: 6.6 x 1.4 x 9.5 inches