I was never a Shaker but I often wondered what it would have been like. I lived in New England for a number of years and volunteered a few summers at Canterbury Shaker Village. I spent hours upon hours in the gardens. One of my jobs was harvesting mints for their special four-mint tea and laying it out in the drying rooms. At the end of the day I was rewarded with an armful of wildflowers, dirty fingernails and a sense of accomplishment. The setting was beautiful and peaceful. The communities offered security, stable shelter, reliable food, excellent education and the most advanced medical facilities of the time. These basic needs were not so common in early America. I could easily see why people would have been attracted to it.

It is one of these situations that brings the protagonist of this novel to a village in 1840s Massachusetts. Polly’s father is a brutish drunk who beats her mother, nearly drowned her baby brother and assaults her on a nightly basis. After a particularly drunken threat, Polly decides to free her family, certain he is going to kill them soon. She sets the house ablaze and gets her mother and brother in a carriage. They escape in the night. Polly’s mother brings the children to the local Shaker community, who readily adopts them. Polly struggles to understand why she is no longer allowed to consider her brother Ben as family, and why her mother abandoned them so entirely. In the midst of this, she befriends an orphan who has been a Shaker her entire life.

The narrative also includes the thoughts of Simon Pryor, an insurance investigator who is called to the burnt home to determine the cause and possibly expedite the sale of the land. Pryor keeps his findings to himself and instead seeks to find Polly for more answers.

Pryor’s portion of the storytelling are the most interesting. His voice is clearly defined and his character is vibrant. Polly is a bit more unsure of herself as a character. At times, it feels that the author set out a plot first, then set Polly along that path, and therefore weakened her motivations to fit it. And the reader’s sympathy for Polly is situational but not emotional.

In general the prose itself is strong. It has a blunt character to it that is appropriate for the setting:

Polly sighed and turned to the final page of her pamphlet, dropping her head in supplication to the rules written out before her. Her candle barely lit the words as she struggled to make them out in the flicker of its flame. She did not wait for the order to read.

It was a poem. She had once loved poems. With words free from precise meaning, they reminded her of dreams. She had found them in books that lined her walls against the cold, books she had borrowed from Miss Laurel, books that had been Polly’s secret. Full of poetry, stories, essays — waking dreams so sacred that not even her mother knew of the fullness they made inside her mind. ~Pg. 179

And from Simon Pryor’s narrative:

I think that I have made it quite plan: I do not believe in Providence. however, I must admit to moments when it seems an invisible hand extends itself and pulls sinners like me up out of the mire. On the particular morning of my salvation, I trundled downstairs after a bath and a shave — even in the dullest of times, one must keep up appearances — to find the corner of a letter peeking out from under my door. I pulled it to me and squinted hard at the print, for though it spread tidily across the envelope — each letter as perfectly formed as the next — it appeared very small indeed. ~Pg. 159

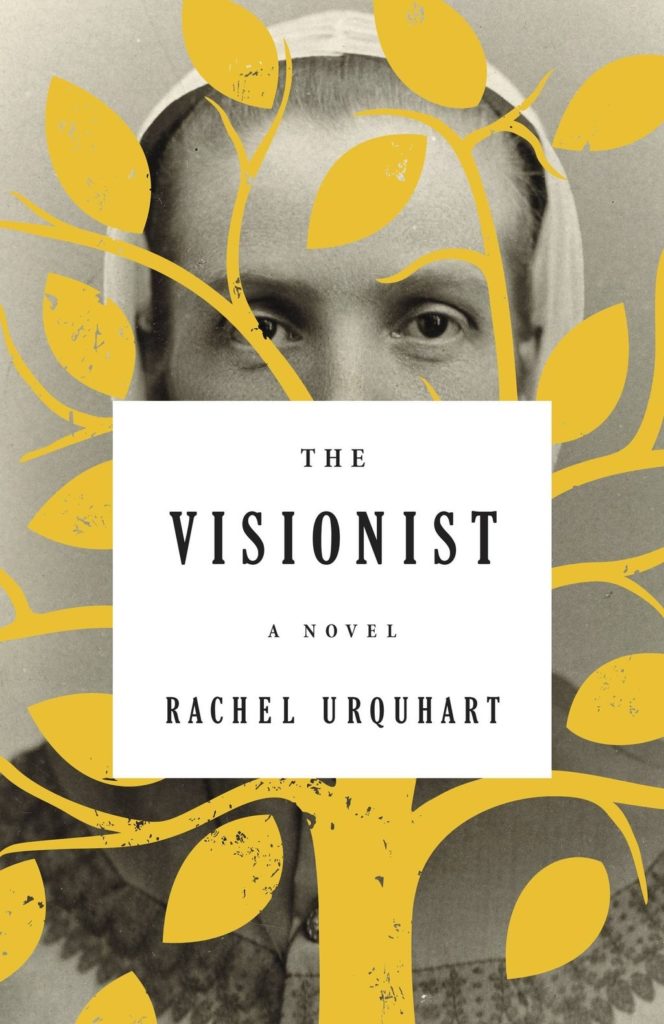

Readers looking for an historical romance (small r) with a bit of soap opera drama will enjoy The Visionist. Though the author has definitely done a great deal of research, the story itself was not quite compelling enough for this reader.

Thank you to Little, Brown for the advanced review copy.

___________

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Price: $26.00 US/$29.00 CAN

Pages: 352

Physical Dimensions: 6″ x 9-1/4″

ISBN-13: 9780316228114

On Sale Date: 01/14/2014

____________

More about the Shakers:

In college, I grew tired of the flippant comment that the Shakers died out because they didn’t procreate. I set out to prove in a term paper that there were a number of factors, including the industrial revolution (and a move to less agrarian society), women’s suffrage, lower mortality rates (and fewer orphans) and a general increase in the standard of living. Havens such as these were no longer leaned upon by the populous. Additionally, many “of the World” believed the Shakers to be possessed, or at least inappropriate, during their ceremonies. Singing raucously, dancing frenetically and sometimes speaking in tongues felt out of place in an industrialized America. As the world modernized and their worship did not, people felt less kinship with the religious aspect of the community.

What many people did not understand then (and many do not now) is that the Shakers were actually very much in favor of technology. They are sometimes assumed to be like the Amish due to their relatively simple, agrarian lifestyle. Shakers were the first to mechanize many of their chores like laundry, weaving and harvesting. They were the first to have cars, electricity, phones (in fact they could only call one another’s buildings for a few years because no one else had a phone). Shakers hold hundreds of patents including the clothespin, the flat broom and the circular saw. Their way of life, though scarce today, is still a fascinating aspect of American history.