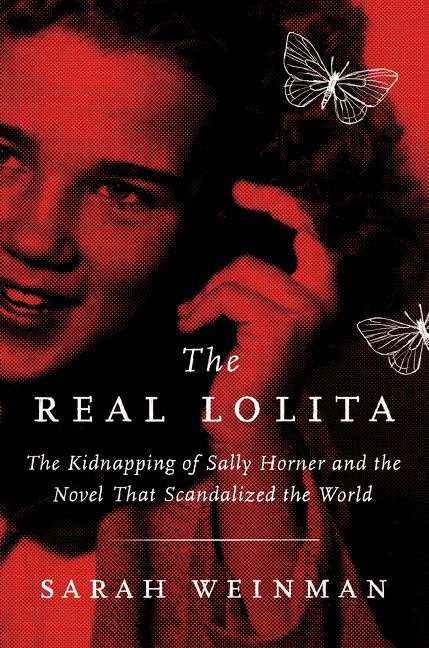

Sarah Weinman, longtime true crime writer and editor of one of my favorite short story collections, traces the story of Sally Horner and its parallels to the novel Lolita. Horner was just eleven in 1948 when she was kidnapped by Frank La Salle. The middle-aged sometimes-salesman coaxed his prey into a two-year road trip across the country. The girl’s disappearance coincided with one of Vladimir Nabokov’s bursts of creative energy.

Weinman found clues to this literary puzzle hiding in plain sight. Humbert, narrator of Lolita, comments on his own likeness to La Salle, but no one had ever pulled the thread to see where it led. Weinman digs through police reports and newspaper articles, and even finds people who knew Sally Horner. She brilliantly lays out the pieces of Sally’s psychology and susceptibility as well as the broken psyche of La Salle.

There are people still alive who remember what happened, but few enough that their recollection are on the cusp on vanishing. Here, in that liminal space where the contemporary meets the past, are stories crying out for greater context and understanding. ~Pg 4.

Weinman also constructs a parallel timeline where Nabokov’s start-and-stop work on Lolita transects the real life crime around Sally Horner. He knew the topic was complicated and that Lolita would be difficult for even the most sophisticated reader. Teaching literature and writing at Cornell and Ithaca during the school year, and chasing butterflies across middle America all summer, Nabokov made notes and sentence drafts on oversize index cards.

Over and over, scholars and biographers have searched for direct connections between Nabokov and young children, and failed to find them. What impulses he possessed were literary, not literal, in the manner of the “well-adjusted” writer who persists in writing about the worst sorts of crimes. We generally don’t bear the same suspicions of writers who turn serial killers into folk heroes. No one, for example, thinks Thomas Harris capable of the terrible deeds of Hannibal Lecter, even though he invented them with chilling psychological insight. ~Pg. 46

Perhaps there was something about knowing the horrible crime had been committed, was already out in the real world, that he wasn’t inventing it, that allowed Nabokov to finally put his novel into a cohesive form.

The Real Lolita is part-history, part-true crime thriller, and part-literary analysis. Weinman makes intelligent conclusions and backs them up with meaningful evidence. She also tells a good story, and brings a bit of warranted attention to the forgotten Sally Horner.

My rating: [icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""]

My thanks to Sonya at HarperCollins for the review copy.