It’s part Treasure Island, part Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a dash of Huckleberry Finn — but Sugar Money is something entirely its own. Told from the point-of-view and voice of Lucien, a barely thirteen-year old farm slave on Martinique, the novel is based on real events. Owned by a group of French priests, Lucien and his older brother Emile are enlisted to go to Grenada and kidnap slaves from the island and bring them back so the friars can increase production of sugar cane and rum.

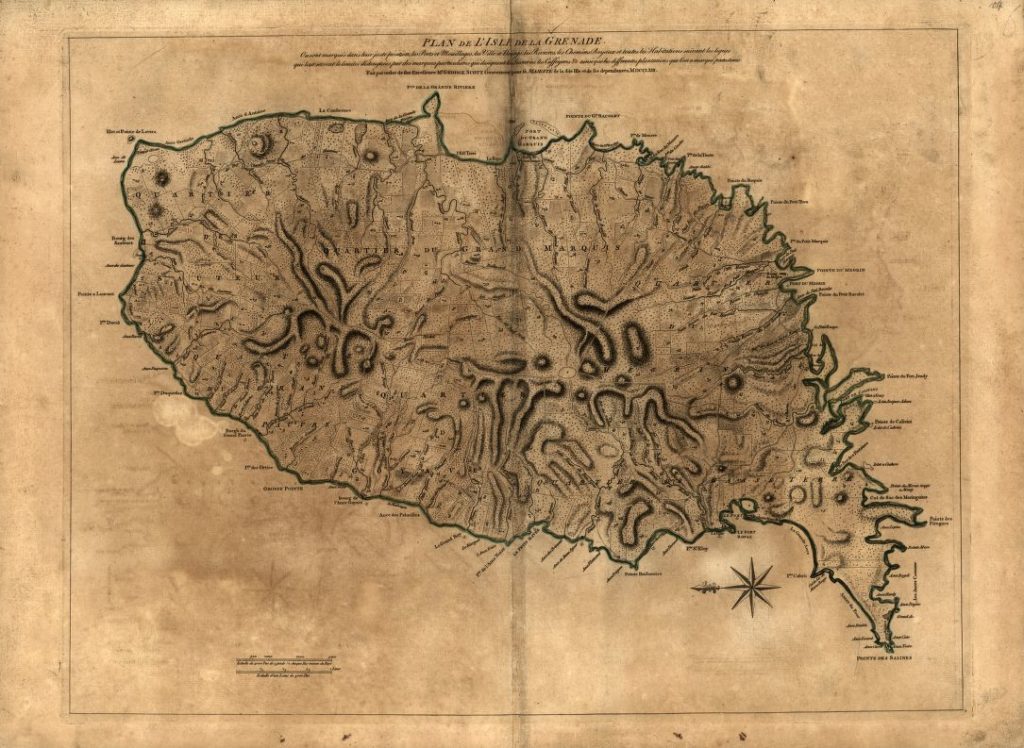

In 1765, Grenada has recently been captured by the English and the priests think the slaves working at the hospital there are under their protection, and therefore can be moved, but the wary priest knows the task will still be dangerous.

For Lucien, it is an adventure and a chance to see the island he used to live on. It is in Lucien’s youthful mind that the reader is allowed to, at times, relish the thrill of the quest. Emile, ever the voice of reason, brings the enormity of the travesty into full view. Harris doesn’t lose sight of this terrible reality. While Lucien sees the sport in outwitting the horrid English, Emile reminds him, and us, that no matter the outcome, none will ever be truly free. Perhaps they will be less abused with at the sugar plantation, but that is the most they can ever hope for.

We had our disagreements, for true, and put each other in a rage with naught more than a single word or glance. Yet, despite all, despite that Emile seem distant or remote, despite his evasions, his mysteries, his temper and his pride, even back then I knew that nobody could break the bond of blood — good and bad — between us. ~Pg. 63

Perhaps most impressive is the distinct voice of Lucien. His first-person narrative is full of idiosyncratic phrases and vivid descriptions. Writing this at a later time in his life, it is assumed that he has since increased his vocabulary but the childlike wonder remains. The exchanges in patois and with slightly incorrect grammar are so grounding in time, place and heritage. Every time I picked the book back up, it took a few paragraphs to get back into Lucien’s cadence, which was unlike anything I’d ever heard.

Author Jane Harris kindly agreed to answer a few of my questions about the story and how she framed the book.

Q: SUGAR MONEY is based on a real incident. How did you first hear about the story? What made you want to write about it?

JANE HARRIS: The idea came from reading a history book, written by Beverley Steele. There’s a small paragraph that describes events that took place in 1765: in Martinique, an enslaved man was ordered by his French masters (mendicant monks) to steal a large number of slaves from Grenada, an island which was, at the time, in the hands of the English. I was struck by the description of what happened and by the predicament of the poor slave who had no choice but to obey his masters and carry out this dangerous task. I’m always drawn to characters on the margins of society. Once I had read the true story, I just couldn’t get this guy out of my head. I found a name for him – Emile – gave him a brother so that he wasn’t bearing the whole weight of the narrative upon his shoulders – and took it from there. It was the character of Emile that motivated me. I wanted to find out who he might have been.

Q: Despite adventurous aspects of the novel, the story is rife with reminders of the horrific history of slavery. How did you approach balancing story-telling with history?

A: I’m not in the business of writing non-fiction history books. I write novels and stories, mostly. Story-telling is the most important thing, to me, even when writing a historical novel. I research endlessly, but you have to hide your research. There should be nothing in this book that wouldn’t be remarked upon or noticed by the narrator. Moreover, this isn’t a slave novel in the conventional sense; a novel that exists primarily to highlight the brutality of the Atlantic Slave Trade. That’s a fundamental part of it, of course, but that wasn’t my mission here. What interested me was the small true story of one enslaved man who was ordered by his masters to steal a group of other enslaved people. Based on what little is known of the true events, I pieced together the clues to make a narrative. Because I knew what had happened in the end, I had to balance the scale of atrocity in events leading up to the denouement.

Q: What do you think about the dilemma of writing about slavery while not being a person of color yourself?

A: I’m very aware of my white privilege and I didn’t take on writing this book without much inward debate on the notion of cultural appropriation. In the end, I asked friends and writers, people of colour, whether I was insane to attempt it. They said that yes, I probably was (ha ha!) but that if the book was good enough, it shouldn’t matter. So I knew I had to write an amazing novel. Good writing is an act of imagination. I believe that writers should be able to write about what they want, even if it is out of their experience. For me, that’s the great challenge of writing.

Q: I was struck how I can hear the incredible voice for the narrator, including the patois that is inserted. How did you find that voice?

A: Lucien’s voice is complicated. By the time he writes down his tale, he speaks French, Creole, and English. He is self-taught, and there’s some evidence that the self-taught use a more sophisticated level of language. I listened to Martiniquan Creole online and in movies, and used dictionaries, lexicons, and books of Martiniquan aphorisms and folk tales to get a feel for the kind of language he might use. Once I had an idea of how he might sound, I wrote a tentative chapter and when that seemed alright, I continued. Of course, I refined the voice as I went along.

Q: Did you travel to Martinique? Do any of the locations remain?

A: In total, over several years, I spent eight weeks in the Caribbean and visited both Martinique and Grenada. By and large, the rural areas described in the novel are much the same as they once were. However, in St. Pierre, Martinique, it was hard to work out where the Fathers’ hospital had been located but after much trial and error I eventually discovered the location, behind the town. The perimeter wall and the entrance gates are still standing but only a small part of the original building remains inside – a low, ruined, arch-type structure. The Sugar Landing in St. Pierre is still there but it’s now a paved walkway rather than a wharf. In Grenada, what was the Fathers’ hospital is now a cemetery with no sign of the hospital building. Down in the valley, where once the sugar plantation lay, a huge circular cricket stand has recently been built.

Jane Harris’ new book Sugar Money comes to America this March.

Hardcover: 400 pages

Publisher: Arcade Publishing (March 20, 2018)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1628728892

ISBN-13: 978-1628728897

[star]