At the end of the Victorian era, the women’s suffrage movement had an unexpected supporter. Sophia Duleep Singh was the daughter of the latest deposed Maharajah of Lahore, in India. As a teenager we was forced to give up his throne to the far-reaching British Empire. In part to prevent an uprising and in part because Queen Victoria respected the young prince, the maharajah was given a generous allowance, a courtesy title and a great deal of leeway in his adopted country.

His daughter, Sophia, grew up in a strange world. She was privileged and beautiful. Her debutante season began with Queen Victoria’s approval. Yet, she knew no one outside of her family with ties to India. She looked like no one except her sisters. Her father was largely absent, having become severely disillusioned as he grew older and came to realize what he had given up in India.

The Duleep Singhs were for decades banned from visiting India. The British were afraid that seeing their former royal family would inspire a coup in Lahore. Finally, as a young woman, Sophia and her sister we allowed to attend an official event. Though she felt a kinship with her homeland, Sophia did not fit in there either. When she returned home, she began to truly engage with the British population and find some meaning for her life.

She lent her name and efforts to the cause of votes for women. She had seen now first hand how people, particularly women, lived in India. She had an idea of what her family lost when it gave up its crown. And she knew how unfairly she had been treated as an outsider and a woman in England — even with her relative wealth and station. Fighting for fairness in the vote seemed an obvious cause.

Though she attended meetings and rallies, petitioned and spoke out on behalf of suffragettes, she was also one of many women actively involved on the streets.

The plan set for 18 November, the date Parliament was due to return, was a simple one. First the women would gather at Caxton Hall, Westminster. They would then divide themselves into contingents not more than a dozen strong. Emmeline [Pankhurst] would depart first, with her hand-picked deputations marching in a tight knot around her. … Sophia, at thirty-four, was by far the youngest suffragette in Emmeline Pankhurst’s nine-woman-strong vanguard. Her breath turned to vapour on the cold autumnal air as she attempted to keep up with the taller women and their longer strides. Although Sophia was used to the company of royalty, she felt awed by her companions that day. ~Pg. 247-8

The ensuing riot and beating was very real and very dangerous.

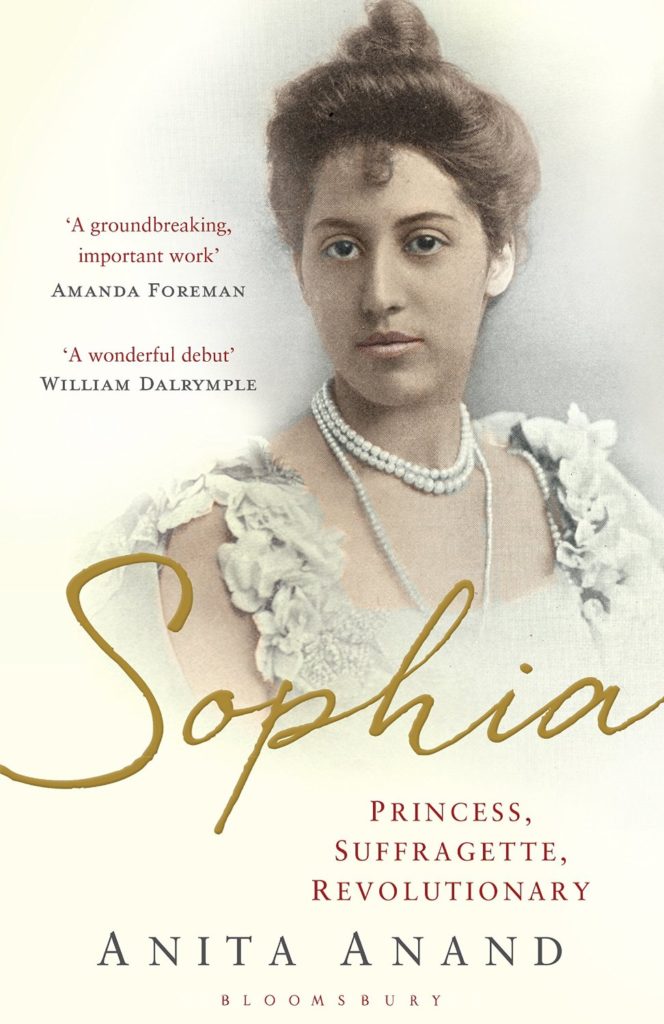

In this portrait of Sophia, Anand shows the reader a person who took command of her own life. The odd circumstances of her birthright were both a stepping stone and a hinderance. Sophia turned it to her advantage.

The book is thoroughly researched and the author does a lovely job of breathing Sophia’s lively personality into the nonfiction sphere. The reader is left with a very definitive opinion of each of the players, no easy feat for a dense and multi-layered biography.

Thanks to Bloomsbury for the review copy.

________

Hardcover: 432 pages

Publisher: Bloomsbury USA (January 13, 2015)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1632860813

ISBN-13: 978-1632860811

Product Dimensions: 6.5 x 1.5 x 9.5 inches