Two hundred years ago, a young woman — barely more than a teenager — wrote a daring novel that questioned the limits of science and discovery, and challenged notions of agency, self, family and moral obligation. Her character created a monster, but she fabricated something much more complicated.

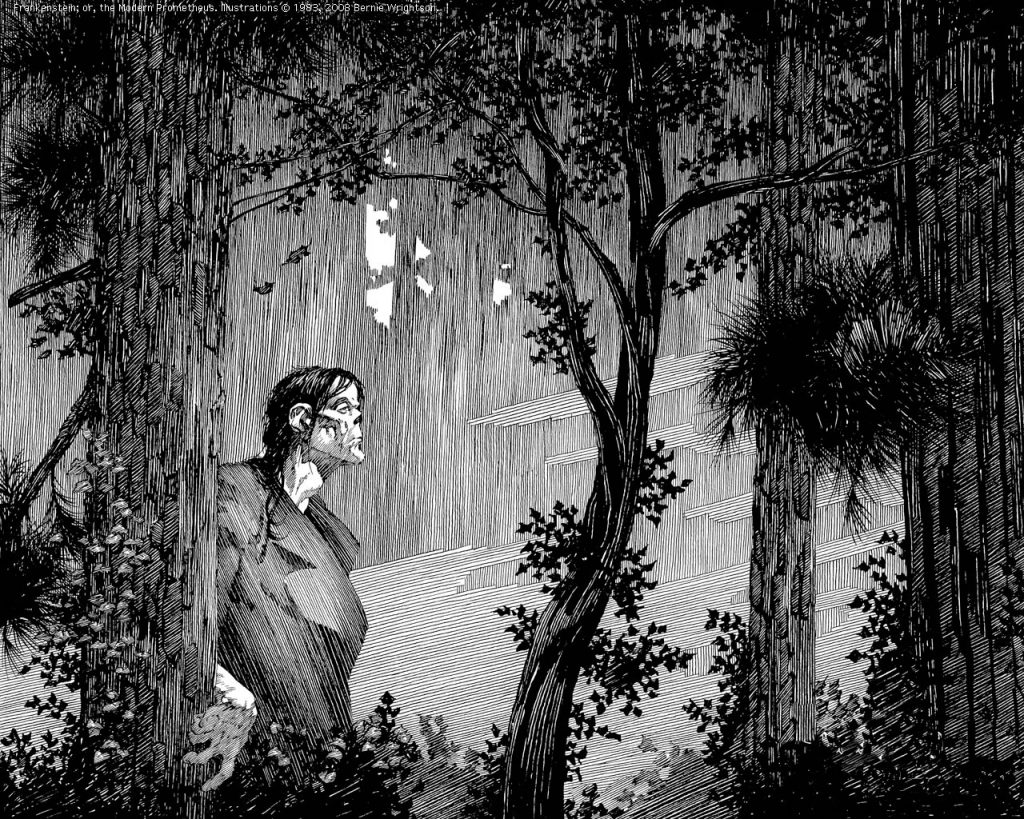

The modern ideas around Frankenstein have been polluted by the early screen versions — a mistake repeated through to contemporary adaptations. While there is some amazing visual spectacle in those horror films, they miss the complex questions posed by Shelley and her groundbreaking book.

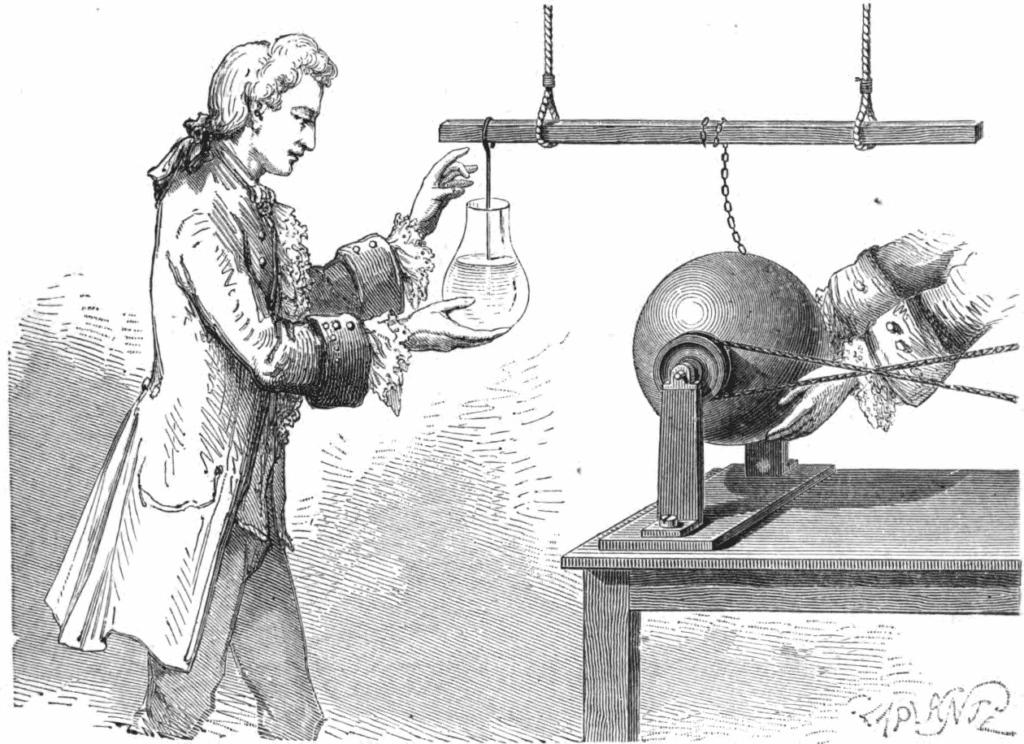

Kathryn Harkup, author of A is for Arsenic, applies a similar process in her previous book to the creation of Victor Frankenstein’s creature. She explores the history of medicine and surgery at that point, the experiments being done with electricity, and galvanism, the exploration of uncharted Arctic territory, and the collision of Enlightenment ideas with Romantic sensibilities.

Harkup is a chemist, by training, but found her stride in talking about the “quirky side” of science. She is limber in her ability to present sound, scientific arguments then bring the reasoning to a lay audience.

However, the idea you may have in your head of an hysterical, obsessive scientist with evil ambitions is very different from the character Mary Shelley created in 1816. The figure she depicted was certainly focused, perhaps even obsessive, about his scientific endeavours, but she did not portray Victor Frankenstein as mad. … Nor is Frankenstein a very good example of science gone wrong. Victor’s experiment in bringing life to an inanimate corpse was a complete success. It was his inability to foresee the potential consequences of his actions that brought about his downfall. ~ Pg. XX

Harkup also weaves in the biographical details that likely affected Mary Shelley and the writing of the book. She traces Mary’s childhood (and even a bit about her radical parents), the strange early courtship of her and Percy Shelley (no matter how many time I read about it, I can’t keep it straight — Byron, Polidori, Clair Clairmont, Fanny Imlay, Harriet Westbrook), and the influences of her acquaintances’ own interests. Shelley had a serious interest in alchemy dating back to his college days. John William Polidori was a medical doctor who liked to discuss the source of the “spark of life.” Indeed, he doesn’t seem to be a very good physician at all and is known today for his early vampiric novel and his connection to Byron, not his advances to medicine.

Mary Shelley acknowledges her reading of Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles), the Romantic poets like Coleridge, advances in surgical practices, tissue grafts and the storage of electrical charges, and the macabre tales of resurrectionists. Harkup also notes some of the differences in the 1818 version, published anonymously, and the 1831 reprint, which included an introduction from the now known Mary Shelley. She even traces the route of the band of travellers as they traipsed across middle Europe during the Year without a Summer, and finds clues as to Mary Shelley’s possible naming inspirations.

Harkup has done not only some fabulous research, she has presented it in a fascinating and well structured way. While it might make the most sense to have read Frankenstein before, it isn’t necessary to enjoy the strange world of early medicine and modern science and how it met the tradition of storytelling to create a new type of literature.

My Rating: [xyz-ihs snippet=”4-and-half-stars”]

My thanks to Bloomsbury for the review copy.

By Kathryn Harkup

The Science Behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Hardcover: 304 pages

Publisher: Bloomsbury Sigma (February 6, 2018)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1472933737

ISBN-13: 978-1472933737

Product Dimensions: 5.3 x 1.1 x 8.5 inches