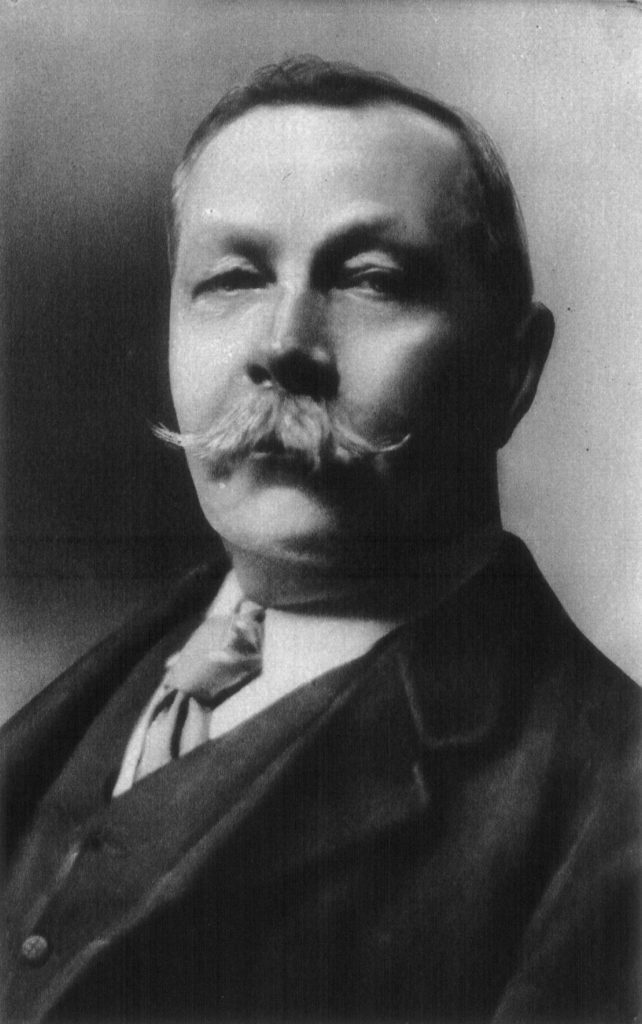

Arthur Conan Doyle, best known for his Sherlock Holmes stories, was an endlessly fascinating person. He trained as a doctor, was a medical officer on Arctic and African voyages, covered the Boer War, brought downhill skiing to Switzerland, investigated spiritualism and fairies, and was friends with Bram Stoker, Harry Houdini, and R.L. Stevenson.

He also cleared the names of two wrongfully convicted men.

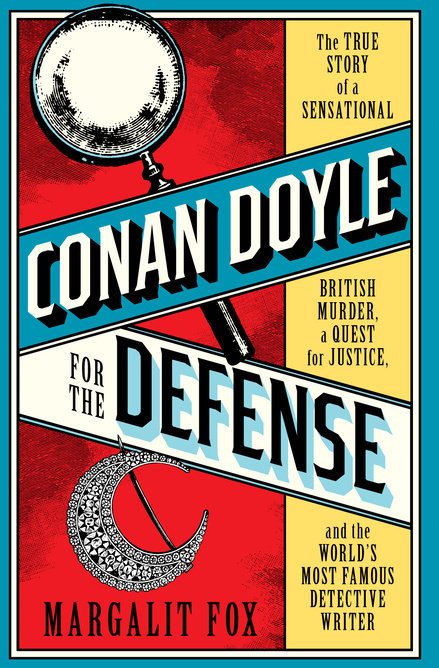

The story of George Edalji has been chronicled, novelized and adapted for television. Less well-known is the 1908 trial and conviction of Oscar Slater, a man accused of killing Marion Gilchrist, a wealthy woman in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded murdered in her home, the police focused on a missing half-moon brooch as the clue to finding the killer. A German Jewish immigrant, going by the name Oscar Slater, recently pawned an item of that description and so the police suspect him. But even after his item is confirmed to be unrelated to the murder, the authorities continue to pursue him.

Slater is caught, tried and convicted, and is sentenced to hang. He receives a royal pardon and is sentenced to hard labor in a desolate, windswept work prison. The story catches the attention of Conan Doyle, other advocates, and the general public, but his conviction is not overturned.

Fox sets out the facts of Slater’s movements as well as the investigator’s reports against the biography of Conan Doyle, his use of abductive reasoning and the famous author’s own writing on the topic. Fox posits that his medical skill, used for diagnosing illness, is integral to his analysis of this case, and his presentation of the facts to the public.

If you want to solve a crime, call a doctor — better still, a doctor who is a crime writer. Detection, at bottom, is a diagnostic enterprise: like many Victorian intellectual endeavors, medicine and crime-solving seek to reconstruct the past through the minute examination of clues. For if the nineteenth century was about the coming of modern science, it was constructive fields like geology, archaeology, paleontology, and evolutionary biology, that let investigators assemble a record of past events through evidentiary traces, often barely discernible, that lingered in the present. ~ Pg. 61

Fox also highlights Conan Doyle’s Victorian morality, a sheer stubbornness when it came to accepting an unfairness. He insisted that Right and Wrong were imperatives and would champion causes to prove his point. It does seem this was often done out of a universal sense of Good vs. Evil, rather than the altruistic take on any individual case. But it is likely Oscar Slater didn’t care why Conan Doyle helped him after he was finally released after 18 and a half years in prison.

The book touches on Poe’s ratiocination, the utter genius of Dr. Joseph Bell, the botched use of the Bertillion system, anti-immigrant sentiment, and how this case became the basis for the first Court of Appeals in the history of Scotland.

It is packed but Fox handles it all deftly, guiding the reader from one detail to the next with clear connections and genuine relevance. The book is well-organized and a very captivating read.

My rating: [icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""][icon name="star" class="" unprefixed_class=""]

My thanks to Mary at Random House for the review copy.

Hardcover: 352 pages

Publisher: Random House (June 26, 2018)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0399589457

ISBN-13: 978-0399589454

Product Dimensions: 5.8 x 1.3 x 8.6 inches