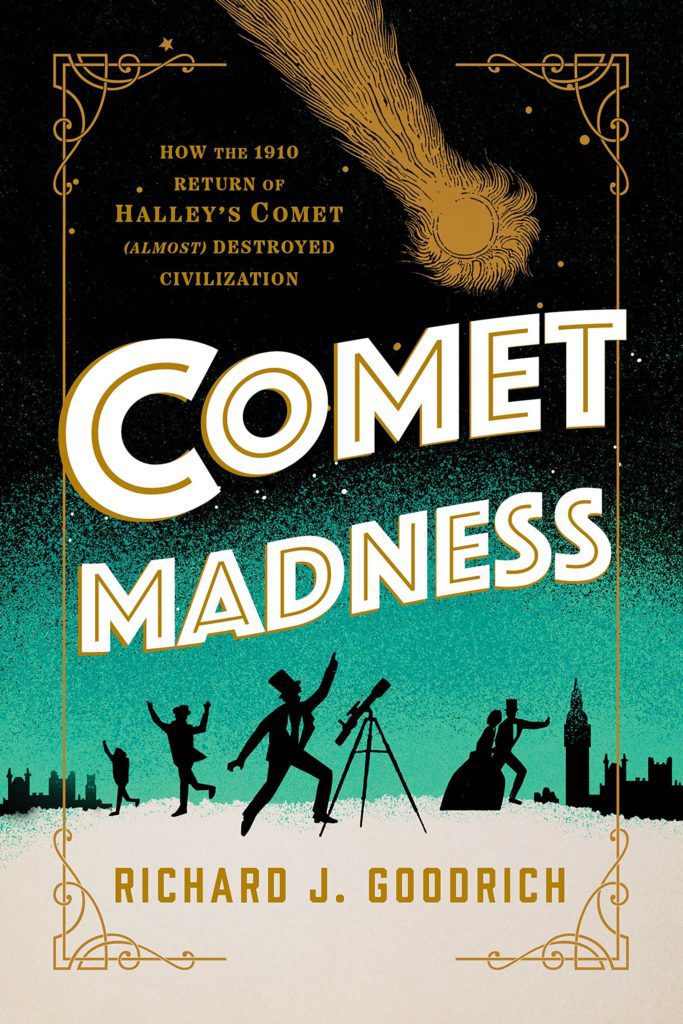

Discovered by Royal Astronomer Edmund Halley in 1758, the celestial body was noted for its predictable perihelion, bringing it close to Earth each 75 years or so. Although it had been making this trip for eons, it was named after Halley as he was the one to formally trace its path and prove that the comet that has been seen for millenia was indeed the same one returning over and over. It last passed by us in 1986 and it will next stop by in 2061.

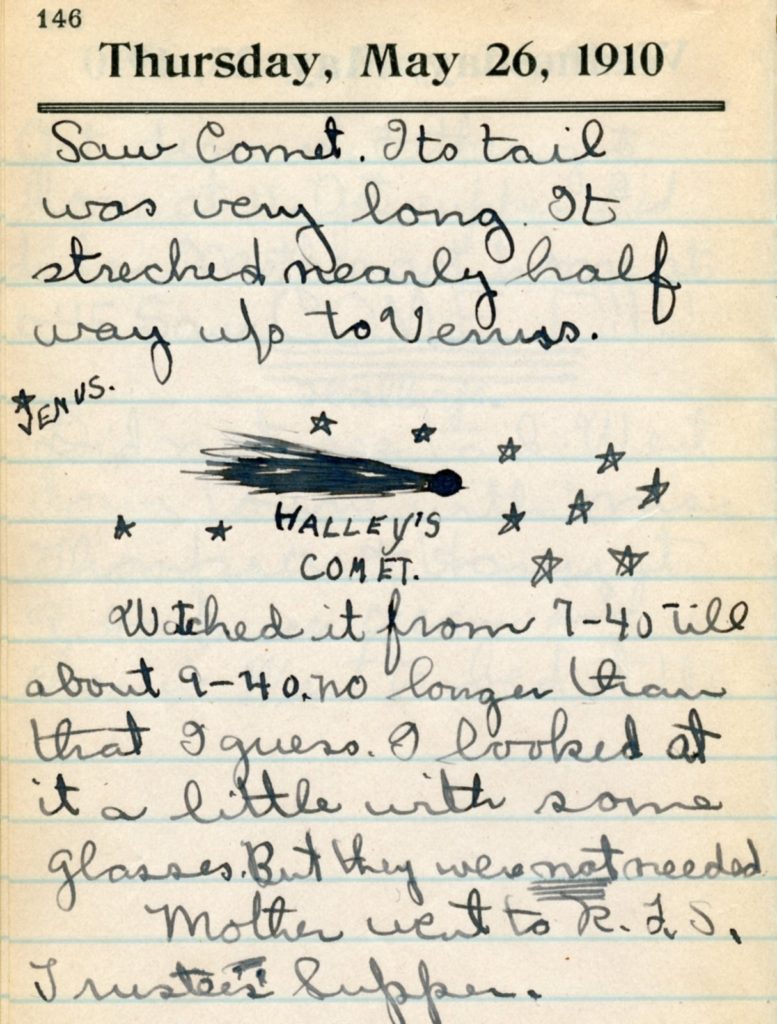

In 1910, the imminent appearance of Halley’s Comet set off an unusual collection of fears, theories, and superstitions. The most prevalent was some variation of a gas cloud as Earth passed through the tail of the comet. This gas might do any number of things, including wipe out all life on the planet.

The book focuses mainly on the media wars surrounding the statements of Camille Flammarion, the preeminent popular scientist of his day. He was based in Paris but his work was read throughout the world.

Flammarion, although capable of calculation, possessed the heart of a poet. He was enthralled by the majesty of the heavens and believed that astronomy was a springboard for the imagination. He preferred speculation about what might be over the dry documentation of what was. ~Loc. 658

But like irresponsible news outlets in every era, greedy editors led with headlines that stoked panic. They took the scientific imaginings of what cyanogen gas might do, in certain circumstances, and turned them into doomsday predictions. It meant that Flammarion spent a good deal of time and ink trying to correct and clarify his analysis.

At times the book loses some momentum as it tracks the media battles. The more interesting sections highlight some of the odder reactions of everyday people. Ads were placed for submarine rides, suggesting people stay underwater for three days (with supplies, of course) until the gas dissipated. Snake oil salesmen sold comet pills that supposedly protected against cyanogen gas. Other enterprising people sold comet insurance…

…policies that promised a cash payment of $500 ‘to the widow or children of the victim in case death is met through the comet striking the earth.’ Policyholders paid 25 cents a week to insure their lives. Although a sensible person might question the value of a policy that paid off only in the event of a world-destroying cataclysm, business was brisk. ~Loc. 2754

Spoiler alert, the world did not end in 1910, nor did it end in 1986. And while there will always be a small contingent of people who go for loony ideas but perhaps looking back we can learn from the past.

My thanks to Prometheus Books for the review copy. Read via NetGalley.

Publisher: Prometheus (February 15, 2023)

Language: English

Hardcover: 282 pages

ISBN-10: 1633888568