How interesting can a book about wallpaper be? Extremely.

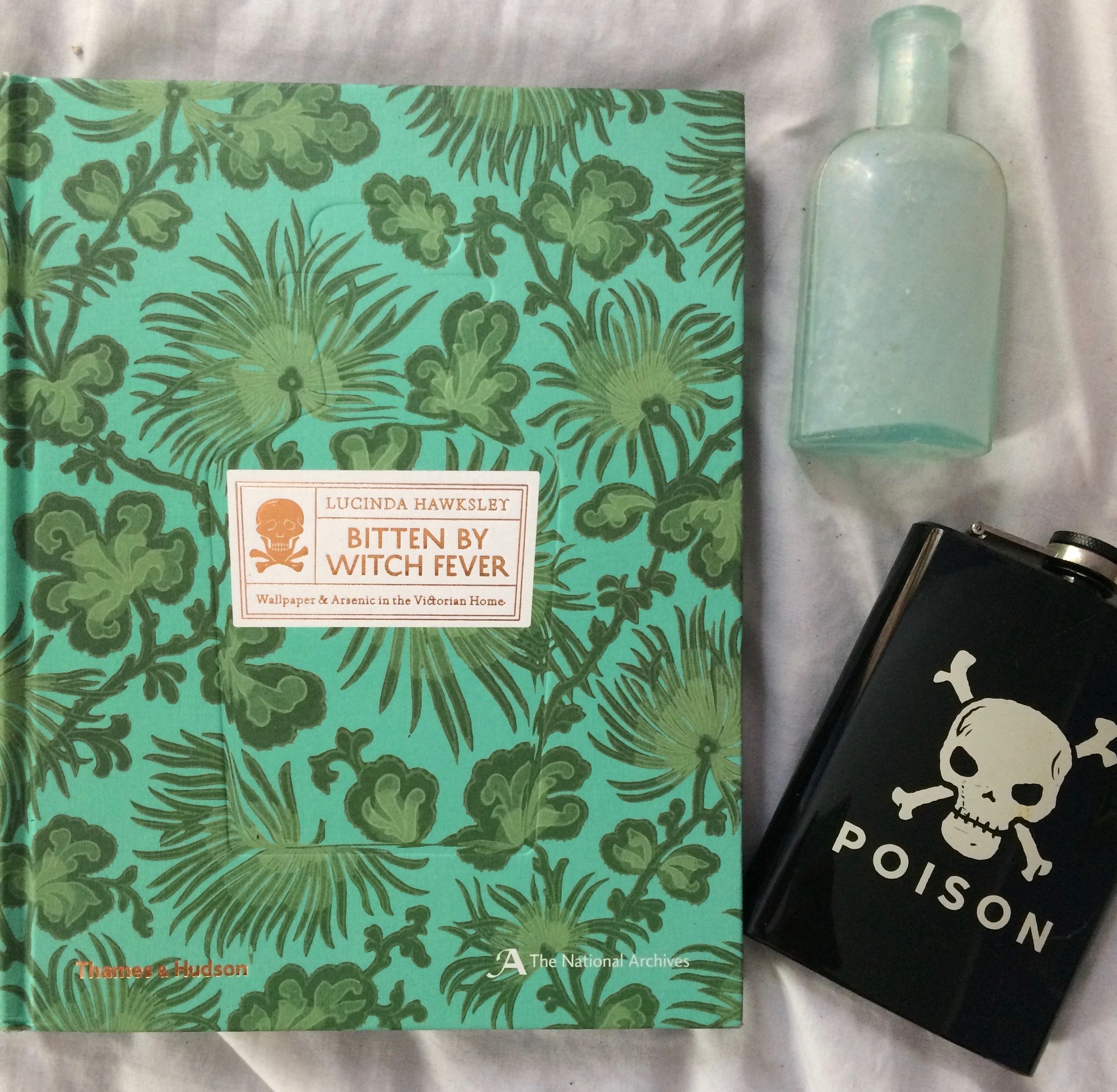

Lucinda Hawksley has written a brief, approachable history of the use of wallpaper and arsenic in the Victorian era.

While Regency decoration favored more muted color palettes, the Victorians embraced bright, gaudy and electric hues. This included the rich fabrics used to make women’s ball gowns and the impressively printed papers hung in parlors and bedrooms across England.

In 1884, the Massachusetts State Board of Health, Lunacy and Charity noted in its annual report that a dress a made from arsenic-green tarlatan might shed twenty to thirty grains of poisonous pigment in just one hour of dancing. ~Pg. 99

Four grains was considered a fatal dose, if ingested.

Hawksley touches on numerous aspects of the phase including the mechanization of wallpaper production, arsenic as a common household item, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, and the reluctance of government to regulate or ban the element’s use.

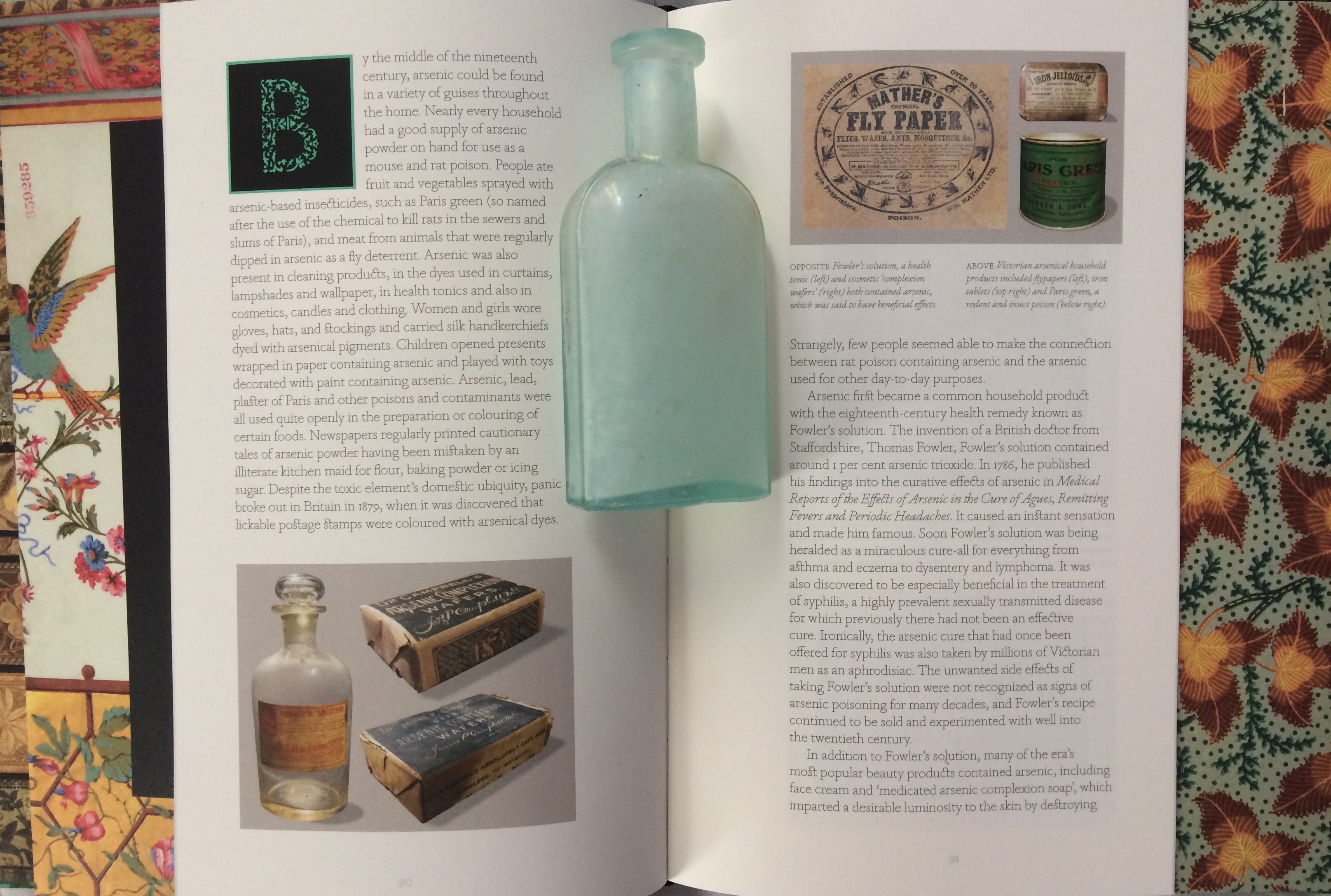

Arsenic was prevalent in face cream, health tonics, spa waters, and rat poison. Newspapers often included items about a cook who accidentally used the white powder instead of flour to make dinner. The same papers also carried ads for medicines containing the same ingredient.

The powder was a byproduct of mining, a trade particularly prevalent in the Industrial Revolution and forward. Miners brought up coal to feed the the quickly expanding railways, and ores to meet the demand of factories springing up across the country. Even while miners were made ill, or killed, by prolonged exposure to arsenic dust, society women were using it to clear up their complexion.

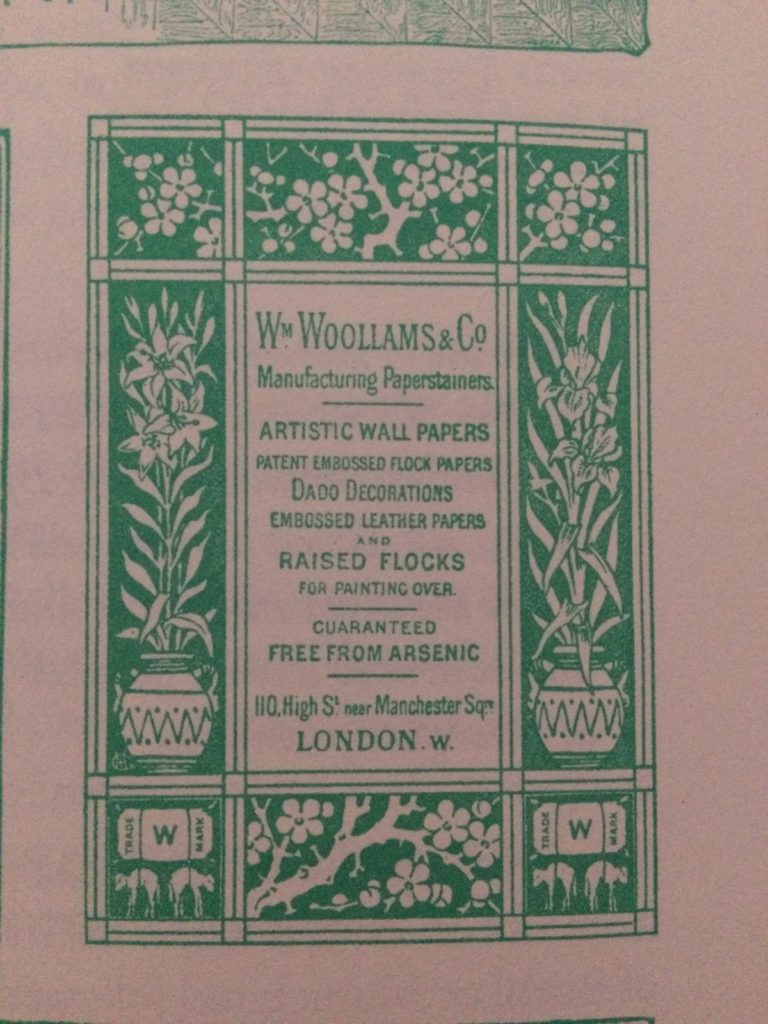

It took dozens of medical reports and hundreds of arsenic-related deaths for wallpaper printed to stop using dyes made with the poison. Though it was never official banned, the public outcry made the decision for them.

Allegedly, in 1879, Queen Victoria was kept waiting at Buckingham Palace by the late arrival of one of her guests. When the dignitary finally made his embarrassed appearance, he looked as though he had come from a hospital ward, not from one of the country’s most prestigious bedrooms. He had been sleeping in a guest room decorated with green wallpaper and had experienced a terrible night of illness. The queen promptly ordered any arsenical wallpaper to be stripped from the palace’s walls. ~Pg. 163

The information included in the book was well-presented and had me looking for more on the subject, but I did want Hawksley to close the loop a bit tighter. How was it discovered that arsenic made pigments brighter? Did it in fact clear the skin? More importantly, was Parliament’s reluctance to ban the material connected to the mining industry? Had those with mining interests found a way to make a profit off of something that was previously only a troublesome byproduct of mining? These would be questions outside of the scope if this were only a book about design history, but it isn’t. It’s an examination of society’s willingness to turn a blind eye to poison and death for beauty.

The book includes hundreds of samples from the National Archives at Kew, all found to contain arsenic. They are beautifully reprinted (safely) here. The designers have also made the text of the book narrower so that the wallpaper art becomes a backdrop as you are reading. It’s a gorgeous volume and fantastic introduction to arsenic in the Victorian home.

My thanks to Thames and Hudson for the review copy.

_____

Format: Hardcover

Pages: 256

Artwork: 350+ illustrations, 250+ in color

Size: 8 in x 10.2 in x 1.1 in

Published: October 11, 2016

ISBN-10: 0500518386

ISBN-13: 9780500518380