With Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle prefigured some forensic techniques that wouldn’t be used for decades. Conan Doyle, a doctor himself and a student of leading medical diagnostician Joseph Bell, drew on his scientific knowledge to imagine ways criminals could be traced and caught. E. O. Heinrich did it in real life. He pioneered a nonexistent field of criminology through innovation, imagination and dogged methodologies.

Building upon Locard’s exchange principle, Heinrich standardized investigation processes, making results more consistent. He also became a respected expert who would testify in trials and conduct groundbreaking experiments for puzzling cases.

Despite this, Heinrich isn’t a household name, or even much of a laboratory name. Dawson’s book may change that. She stumbled across his name while reading an encyclopedia entry. Surprised she had never heard of the “American Sherlock Holmes,” she dug deeper. She learned his massive collection was a UC Berkeley. Unfortunately it was so large it hadn’t been cataloged yet and she wouldn’t have access to it. Until she convinced the archive librarian to take a peek. Thankfully for all of us, she too became interested in Heinrich and agreed to tackle the project.

Using these files full of notes, bits of evidence, reports, scribbles, journals and photographs, Dawson puts together a timeline of Heinrich’s cases and personal life. She also doesn’t shy away from noting his failures as well as his significant successes. Heinrich becomes flawed, brilliant, and human.

Heinrich worked on the Fatty Arbuckle case and the Great Train Heist of Oregon. He chased serial killers and missing persons. He even led investigators to new clues in a case of corporate espionage turner murder.

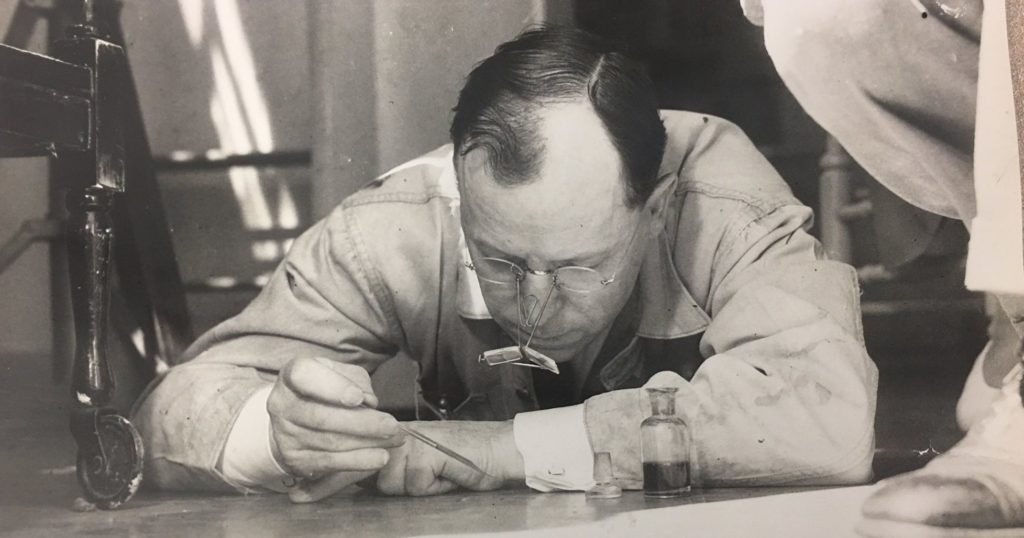

The special agents spent days in the interrogation room with no results, and now they needed Oscar Heinrich to glean anything he could from the items. The criminalist began by examining a .45-caliber pistol, a brown canvas knapsack, burlap show coverings, and a plaid of blue denim bibbed overalls. The agents explained that as many as twenty other experts had investigated the clues, and other than mechanic’s grease, there were no important discoveries. As his assistant escorted the investigators to the door, Oscar turned to his desk. ~Pg. 147

The book is more of a biography, with some forensic science history, than a true crime treatise. The case files and crime scenes are seen as part of Heinrich’s day-to-day life rather than events in themselves.

It’s truly incredible to see just how many techniques he started, even if the practices has had to be perfected over the years. Heinrich wasn’t perfect. He made mistakes, and some of the mysteries remain unsolved. But in his few decades on the case made a dramatic impact on the field.

The book took a few pages to really get going, but once it did I was hooked. There were also instances where the author appeared to have written the chapters as separately and didn’t quite stitch them together. Occasionally phrases or descriptions were repeated with little or no variation. Other than these tiny details, I thoroughly enjoyed the book.

My rating: [xyz-ihs snippet=”4-and-half-stars”]

My thanks to GP Putnam for the advance review copy.

Hardcover: 336 pages

Publisher: G.P. Putnam’s Sons (February 11, 2020)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0525539557

ISBN-13: 978-0525539551