Biographer, editor and man of letters Michael Sims agreed to let me pick his brain about Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes, a fascination we share. Sims was a distinguished speaker at the Baker Street Irregulars annual gathering in 2011. Sims’ newest book, Arthur and Sherlock, comes out January 24.

Biographer, editor and man of letters Michael Sims agreed to let me pick his brain about Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes, a fascination we share. Sims was a distinguished speaker at the Baker Street Irregulars annual gathering in 2011. Sims’ newest book, Arthur and Sherlock, comes out January 24.

Q: Did you read Sherlock Holmes as a child?

A: I think I first encountered Holmes and Watson in my school lit textbook around 1971, the year I turned 13. Then, only a couple of years later, I insisted that my mother order for me, for Christmas, William Baring-Gould’s classic Annotated Sherlock Holmes. Baring-Gould opened up the world of literature and history for me and made it all seem layered and dense with connections. It was a very significant discovery for me.

Q: I know I am surprised every time I reread the stories how much more there is to discover. What did you think of him then vs. now?

A: Now I can appreciate all the many ways that Doyle created Holmes as both a Romantic hero and a scientific man of his time—a cross between Robin Hood, Poe’s detective Dupin, Gaboriau’s detective Lecoq, and his medical school professor, Joseph Bell back in Edinburgh. At this time—he hadn’t yet turned toward the buffoonery of his spiritualist decades—Doyle was a big fan of scientific thinking. He admired Darwin and Huxley. He saw Holmes as a scientific hero.

Q: You seem to gravitate toward classics and Victorian literature, both as an editor and a biographer.

A: Yes, lately I spend a lot of time in the nineteenth century. I keep finding myself drawn to the giddy sense of discovery that prevailed in the sciences and the arts during that curious, outrageous, pious, irreverent, imperial, revolutionary era. Just think how much happened between Alessandro Volta’s discovery that electricity could be chemically generated and the Wright Brothers demonstration of heavier-than-air flight. So many of my favorite historical figures cavort there, often rubbing shoulders: Darwin, George Eliot, Huxley, Thoreau, Dickens, Verne, Stevenson, Caroline Herschel, Lister, Daguerre. A time of glorious innovation in literature, the natural sciences, visual arts. Why I was first drawn there I don’t know, but it has opened up a lifetime of exciting reading — and a career.

Q: Why did you choose Arthur and Sherlock?

A: I’ve read a lot about Holmes and his creator over the years. Often the articles and books have been full of interesting information but not thrilling to read. Several are lively, some chatty and amateurish, a few so indigestibly dry they make me cough. I wanted to tell a true story — the emphasis on narrative, with events and dialogue and texture and atmosphere — of those tributary aspects of Arthur Conan Doyle’s experience that fed into two united threads: Doyle’s initial conjuring of a figure who would become one of the most famous fictional characters in the world, and the compositional process by which Doyle turned this inspiration into literary reality. One is inspiration, the other creation. Thus I stay on those themes. I don’t ignore the rest of Doyle’s life, but I use it as background for my story.

Q: Sherlock has never been out of print. He’s been played by more than 200 actors on film and TV. He’s inspired video and board games and even forensic methods. Why do you think the stories still resonate today? Do you think Arthur Conan Doyle would be happy? Or would he have rather left a cold trail at the Reichenbach Falls?

A: I think he would be thrilled. He might pretend otherwise, but he would love it, and he would think he deserved it. He was not a modest man, however much he might pretend to be at times.

Q: Of course Sherlock is the star, but I’ve always had a soft spot for Watson and feel bad when he is portrayed as a bumbling idiot on screen. What are your thoughts on Watson as Doyle created him? Was it in his own image? Is Watson loyal to a fault?

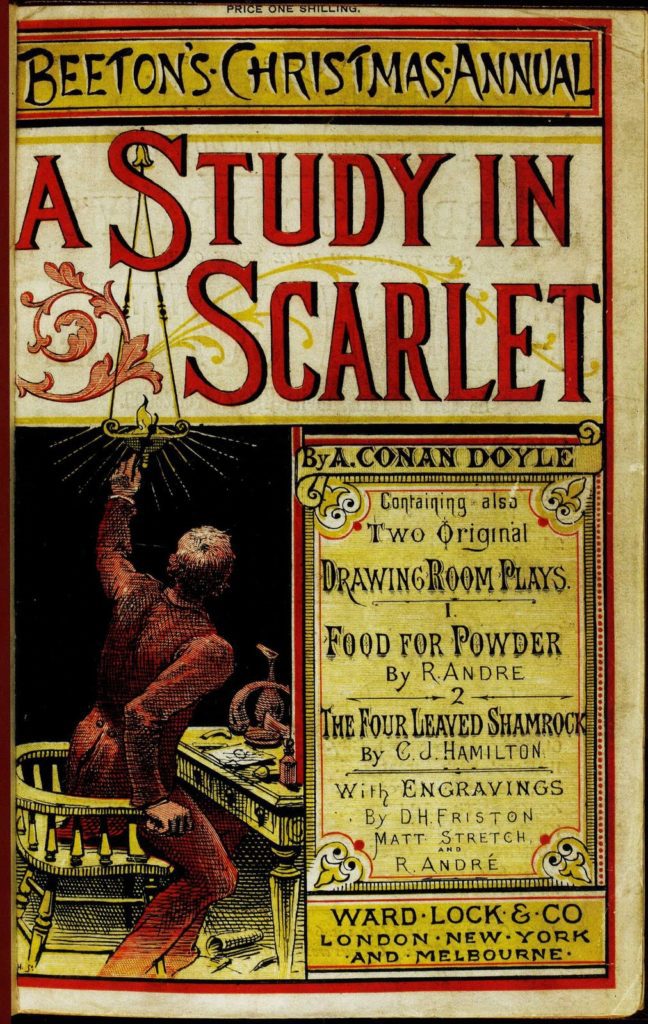

A: I think Doyle had, for one thing, great narrative instincts. He realized that Edgar Allan Poe’s narrator in his three Auguste Dupin stories was a doting nonentity. Thus, despite owing so much to Poe, Doyle began the whole series with Watson appearing first, in A Study in Scarlet — a young man, a wounded veteran, simply looking for a roommate because his only income is a military pension. So he’s normal; he’s young and hurt and lonely and broke. We sympathize with him immediately. Then he leads us to this fascinating, heroic figure. It’s like going through the back of the clothes wardrobe to Narnia, the way that Watson leads us into these outrageous adventures as sidekick to a wizard.

And Doyle knew that telling stories from Holmes’s own point of view would, first, make his arrogance unbearable rather than amusing, and second, result in readers figuring whodunit too soon.

So Watson is a brilliant narrative choice in so many ways. He has a dry sarcastic way of referring to and speaking with Holmes; he is skeptical of the master’s genius even before we are. The good doctor is tough and brave and more rugged than he realizes. A great character. I think I ought to have dwelt on him more in my book.

Q: After reading your book, I have an even greater appreciation for Dr. Joseph Bell. I used to think that he and Doyle were “ahead of their time,” but now I’m not so such. I think perhaps they were each perfectly “of their time” and that’s why they were so successful. What are your thoughts?

A: I think you’re right. They were very much of their time; those who were ahead did not lead lauded, celebrated lives. Bell was one of several deservedly famous diagnosticians such as his contemporary Ferdinand von Hebra in Austria. Each attracted adoring students and became legendary in their field and sometimes throughout European medicine. Hebra, for example, was a dermatologist; he observed occupational stigma better than anyone had before. With few technological aids, diagnosticians needed to re-establish the essential discipline of attentive first analysis.

And Conan Doyle came along at exactly the right time, in many ways. His imagination took off from a rich and thriving field of crime fiction, and latched onto his own personal experiences in medical school with Dr. Bell. He benefited from the flourishing magazine industry at the time, from technical advances, illustrated stories, quick distribution by trains—and a welcoming response to his recreation of the man of action as a man of science.

Q: Have you ever tried to solve a mystery using Holmes’ methods?

A: Yes. I failed abominably every time. A friend once said that I might be trying to figure out where a man was walking, by peering keenly at the mud stains on his shoes, and I would not notice that he wasn’t wearing pants. So now I pretty much limit myself to trying to follow fox tracks in the woods.

Q: Lastly, for fun, do you play “The Game”?

A: For those readers unfamiliar with this topic, I’ll explain that Sherlockians slyly (but it must be straight-faced) refer to Doyle’s writings as the Sacred Writings or the Canon and they pretend they’re all true, that Doyle was Watson’s agent, and so on. “The Game” is the tongue-in-cheek attempt to resolve discrepancies in the stories that actually result from Doyle’s slapdash compositional methods—oddities such as Watson’s migratory war wound. And no, for some reason this sort of game doesn’t attract me, although some of the classic entries in this field are hilarious, such as Rex Stout’s “Watson Was a Woman.”

I am so grateful to Michael Sims for letting me ask him such nerdy questions about some of my favorite historical figures. He so kindly answered each one thoughtfully and with humor.

Read my full review of Arthur and Sherlock.

My thanks to Sarah at Bloomsbury for the review copy.

Published: 01-24-2017

Format: Hardback

Edition: 1st

Extent: 320

ISBN: 9781632860392

Imprint: Bloomsbury USA

Illustrations: 1 x 8-page B+W insert

Dimensions: 6 1/8″ x 9 1/4″

List price: $27.00