T.S. Eliot said that “April is the cruelest month.” It is also National Poetry Month, an effort spearheaded by the Academy of American Poets to highlight the writing form and infuse it into the everyday. The annual celebration is now championed by publishers, library associations, school systems and arts foundations. Its popularity has spread to neighborhoods and businesses who mount poetry flash mobs and participate in Poem in Your Pocket Day. Most importantly, it’s a reminder that there is a type of poem for every reader.

Before Conrad Aiken was the U.S. Poet Laureate or the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, the Bollingen Prize, the National Book Award, the National Institute of Arts and Letters Gold Medal, and the National Medal for Literature, he was a young boy growing up on Oglethorpe Avenue in Savannah, Ga. Born in 1889, he said of his childhood, “In that most magical of cities, Savannah, I was allowed to run wild in that earthly paradise until I was nine; ideal for the boy who early decided he wanted to write.”

His idyll would be dissolved in a moment when his parents were killed in murder-suicide in 1901. The motive was never discovered.

Aiken was taken in by a great-aunt in New England and afforded the best education. But the lilt of a Southern drawl never seemed to leave his ear. His early poetry especially mimics the sing-song cadence of the local accent. In theme, the influences of classic poets like Coleridge, Wordsworth and Poe are evident, yet Aiken’s voice remains his own.

“The Vampire”, a whirling, spooky poem by Aiken, is reminiscent of a scene from “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” when a ghost ship carrying a pale female figure both tempts and repulses the lost sailors. His home on Oglethorpe Avenue, still there, overlooks Colonial Park Cemetery, no doubt a playground for a busy neighborhood boy by day, and a silent, eerie view at night.

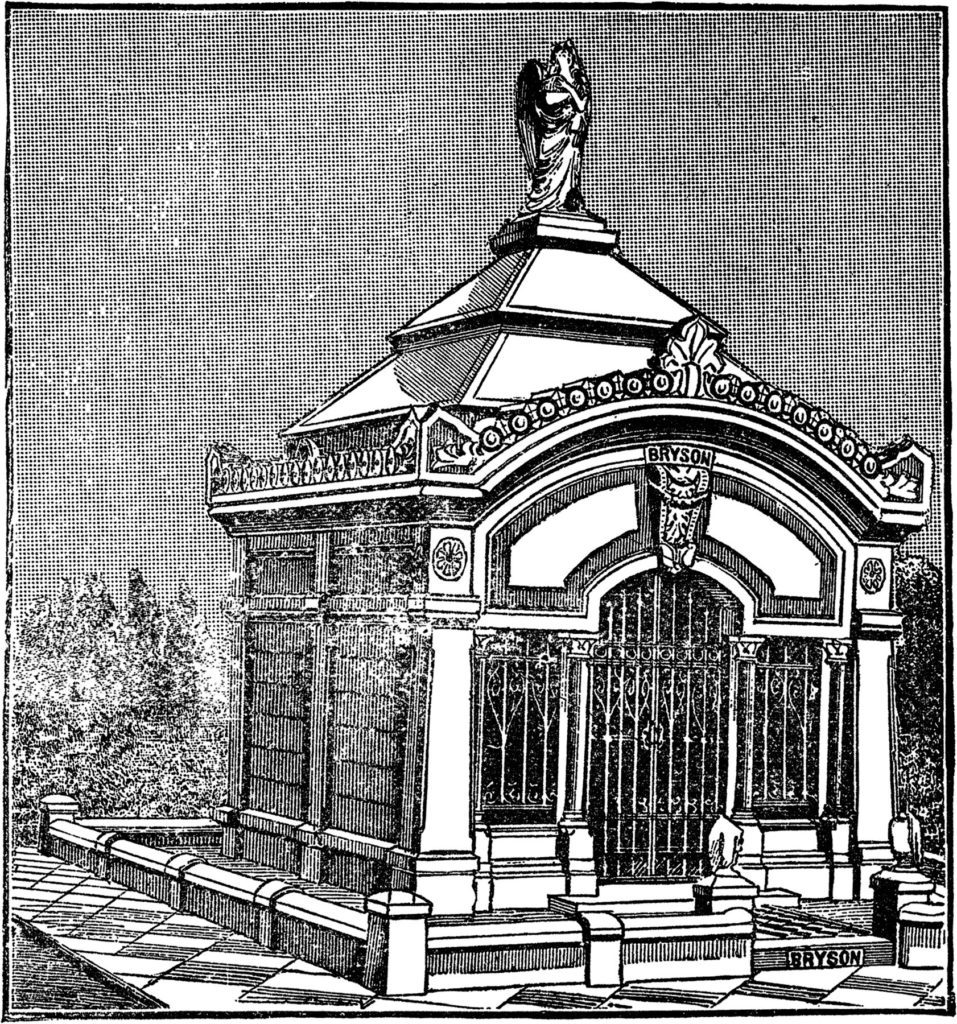

In true Southern Gothic fashion, Aiken returned to Savannah in the 1960s, living in the house next door to the one he’d grown up in. In his last years, so the story goes, he would go out to the river and watch the ships come in. He saw one with a particularly unusual name and looked for its origin and terminus, but found none. Today, visitors to Bonaventure Cemetery are encouraged to sit on his grave, a granite bench inscribed with the epitaph “Cosmos Mariner – Destination Unknown.”

—

The Vampire (1916)

Conrad Aiken

She rose among us where we lay.

She wept, we put our work away.

She chilled our laughter, stilled our play;

And spread a silence there.

And darkness shot across the sky,

And once, and twice, we heard her cry;

And saw her lift white hands on high

And toss her troubled hair.

What shape was this who came to us,

With basilisk eyes so ominous,

With mouth so sweet, so poisonous,

And tortured hands so pale?

We saw her wavering to and fro,

Through dark and wind we saw her go;

Yet what her name was did not know;

And felt our spirits fail.

We tried to turn away; but still

Above we heard her sorrow thrill;

And those that slept, they dreamed of ill

And dreadful things:

Of skies grown red with rending flames

And shuddering hills that cracked their frames;

Of twilights foul with wings;

And skeletons dancing to a tune;

And cries of children stifled soon;

And over all a blood-red moon

A dull and nightmare size.

They woke, and sought to go their ways,

Yet everywhere they met her gaze,

Her fixed and burning eyes.

Who are you now, —we cried to her—

Spirit so strange, so sinister?

We felt dead winds above us stir;

And in the darkness heard

A voice fall, singing, cloying sweet,

Heavily dropping, though that heat,

Heavy as honeyed pulses beat,

Slow word by anguished word.

And through the night strange music went

With voice and cry so darkly blent

We could not fathom what they meant;

Save only that they seemed

To thin the blood along our veins,

Foretelling vile, delirious pains,

And clouds divulging blood-red rains

Upon a hill undreamed.

And this we heard: “Who dies for me,

He shall possess me secretly,

My terrible beauty he shall see,

And slake my body’s flame.

But who denies me cursed shall be,

And slain, and buried loathsomely,

And slimed upon with shame.”

And darkness fell. And like a sea

Of stumbling deaths we followed, we

Who dared not stay behind.

There all night long beneath a cloud

We rose and fell, we struck and bowed,

We were the ploughman and the ploughed,

Our eyes were red and blind.

And some, they said, had touched her side,

Before she fled us there;

And some had taken her to bride;

And some lain down for her and died;

Who had not touched her hair,

Ran to and fro and cursed and cried

And sought her everywhere.

“Her eyes have feasted on the dead,

And small and shapely is her head,

And dark and small her mouth,” they said,

“And beautiful to kiss;

Her mouth is sinister and red

As blood in moonlight is.”

Then poets forgot their jeweled words

And cut the sky with glittering swords;

And innocent souls turned carrion birds

To perch upon the dead.

Sweet daisy fields were drenched with death,

The air became a charnel breath,

Pale stones were splashed with red.

Green leaves were dappled bright with blood

And fruit trees murdered in the bud;

And when at length the dawn

Came green as twilight from the east,

And all that heaving horror ceased,

Silent was every bird and beast,

And that dark voice was gone.

No word was there, no song, no bell,

No furious tongue that dream to tell;

Only the dead, who rose and fell

Above the wounded men;

And whisperings and wails of pain

Blown slowly from the wounded grain,

Blown slowly from the smoking plain;

And silence fallen again.

Until at dusk, from God knows where,

Beneath dark birds that filled the air,

Like one who did not hear or care,

Under a blood-red cloud,

An aged ploughman came alone

And drove his share through flesh and bone,

And turned them under to mould and stone;

All night long he ploughed.

This poem is in the public domain.