Kate Summerscale has once again uncovered a fascinating story from the ever contradictory Victorian era. Not so very long ago, divorce was nearly impossible (unless you were King Henry VIII, of course). Until 1858, “marriage could only be dissolved by an individual Act of Parliament, at a cost prohibitive to almost all of the population. The new Court of Divorce and matrimonial Causes was able to sever the marital bond far more cheaply and quickly.” The case brought forth by Mr. Henry Robinson is one of the first the court hears.

Isabella was already a widow (her husband “went mad”), with a significant dowry and inherited property, at age 31 when she wed Henry Robinson. Henry was a civil engineer — respectable, if not overly impressive. They had two children together and Henry built a sizable home, called Balmore House, for the family.

http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1934709

Yet Isabella was not content. Far from it. She was smart, inquisitive and tenacious. She wanted to be surrounded by thinkers and artists. And she wanted to be loved, not tolerated or used. What sounds perfectly reasonable today was radical 150 years ago. Intelligent women were tolerated, within certain limits, and only when it didn’t interfere with duty.

Like many 19th century people, Isabella Robinson kept a diary. Summerscale writes:

By 1850 the Letts company was selling several thousand diaries a year, in dozens of different formats. These were the books in which Isabella wrote; they came bound in cloth or in red Russian calf hide, which gave off a faint scent of birch bark, and couple be fitted with protective covers and spring locks. ‘Use you diary with the utmost familiarity and confidence,’ Letts counselled the novice diarist, ‘conceal nothing from its pages nor suffer any other eye than your own to scan them.’ …

Women, in particular, took to diarising with a passion. … The act of diary-keeping honoured many of the values of Victorian society — self-reliance, autonomy, the capacity to keep secrets. But if taken too far, these same virtues could turn to vices. Self-reliance could become radical disconnection from society, its codes and rules and restraints; secrecy could curdle into deceit; self-monitoring into solipsism; and introspection into monomania. Pages 152-4

In this case, her diary did more damage than she could have imagined. As her marriage became increasing unhappy, Isabella wrote of secret and exciting interactions with other male figures in her life. She admitted to being miserable, to wishing she could leave her despicable husband. While in the throes of a life-threatening fever, Henry finds her diary, reads it and decides to use it against her in court.

Not only was Isabella Robinson subjected to the humiliation of begin taken to divorce court, her innermost thoughts were read in court, transcribed by the newspapers. In her letters during the time she seems to be almost in denial that anyone could use private thoughts and ideas as evidence. She sounds frustrated but confident that common sense will win out. Yet a conundrum seems to be all that Isabella faces. She is encouraged by friends to claim madness, that he writings were nothing but hallucinatory. No answer is satisfactory. If she claims they are imaginings, then she is mad. If she claims the entries to be true, then she must be mad to have written them down.

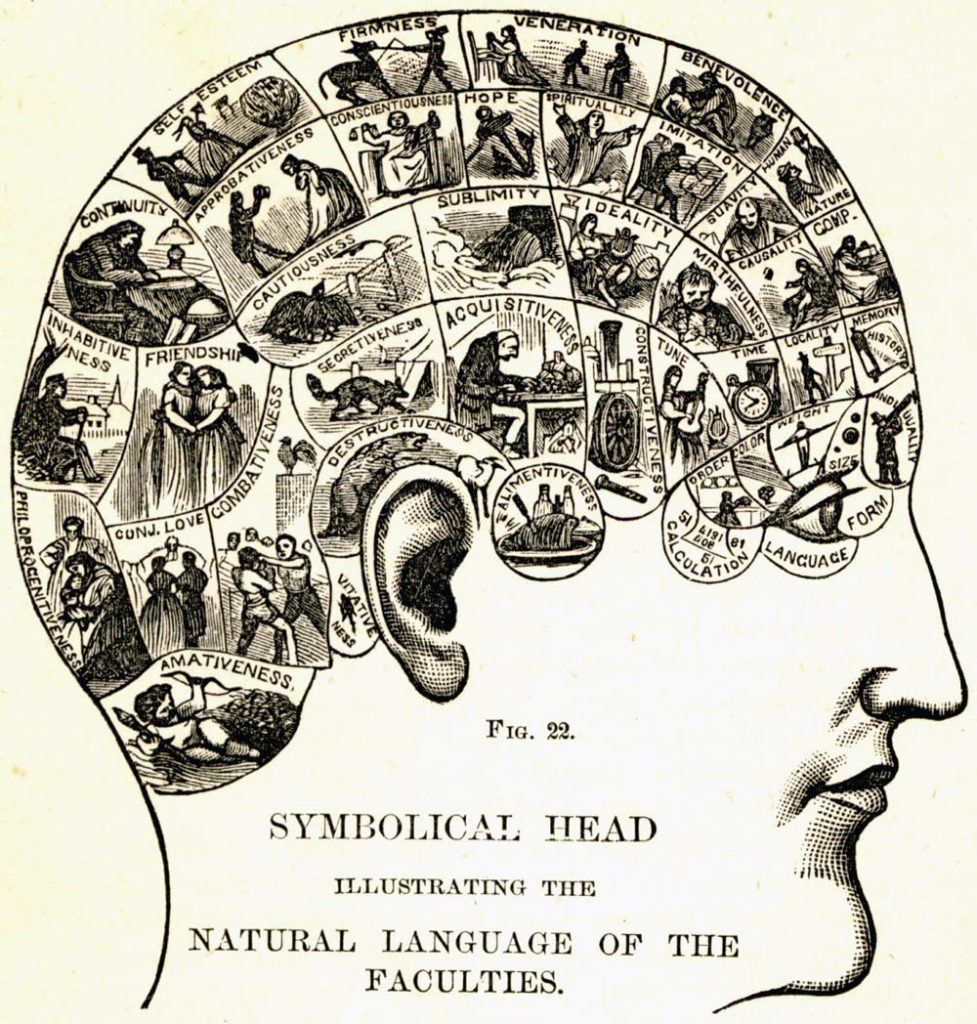

Even while Isabella Robinson had involved conversations with Charles Darwin, was good friends with phrenologist George Combe, and was related by marriage to William Wordsworth. Yet she was also considered a poor example of womanhood. Despite her efforts to find some sort of peace within her unhappy life, she was left to be embarrassed by a society that would rather not accept her.

Summerscale’s research is impeccable. Several pages are devoted to notes with extra tidbits of information. She completely encapsulates the strange grey area that was the Victorian era. She has combed through thousands of letters, newspaper articles, and yes, diaries, to paint as complete a picture as possible. And despite the title of the book, does not use Isabella’s diary as a source for salacious tidbits, like tabloids would have. It is just one reference point for a greater portrait.

Many thanks to Bloomsbury for the review copy.

__________________________________________

June 2012

$26.00

384 pp

5.5 x 8.25 in

Hardcover

ISBN-13: 9781608199136

ISBN-10: 1608199134