I have a weakness for house museums — the odder the better. So often these homes have been saved by a stalwart group of enthusiasts, run by a small staff, and determined volunteers. And while the massive institutions that house national treasures can be overwhelmingly impressive, I find the ability to immerse myself in a more specific and (usually) less pretentious setting more enjoyable.

Sir John Soane’s House

Soane was the son of a bricklayer who used his connections to learn about building, architecture, materials and more. He displayed a significant aptitude for the topic and attended the Royal Academy. Winning various awards and scholarships, he took a Grand Tour and visited the world’s most notable structures. His obsession for Neoclassicism was stoked even further and he brought back pieces and casts of old world art.

Currently the museum occupies 12, 13 & 14 Lincoln’s Inn Field. Soane first bought No. 12, demolished and rebuilt it to his liking. Over the years, he did the same with Nos. 13 and 14 and interconnected them. Notably, the house is how he lived in it. Each room is overflowing with antiquities, organized as only Soane could have imagined.

Soane eventually became an architect of note, working on the Bank of England, Dulwich Picture Gallery, St. Peter’s Walworth, Whitehall Treasury, Royal Hospital Chelsea, and more. He was knighted in 1831.

Emery Walker’s House

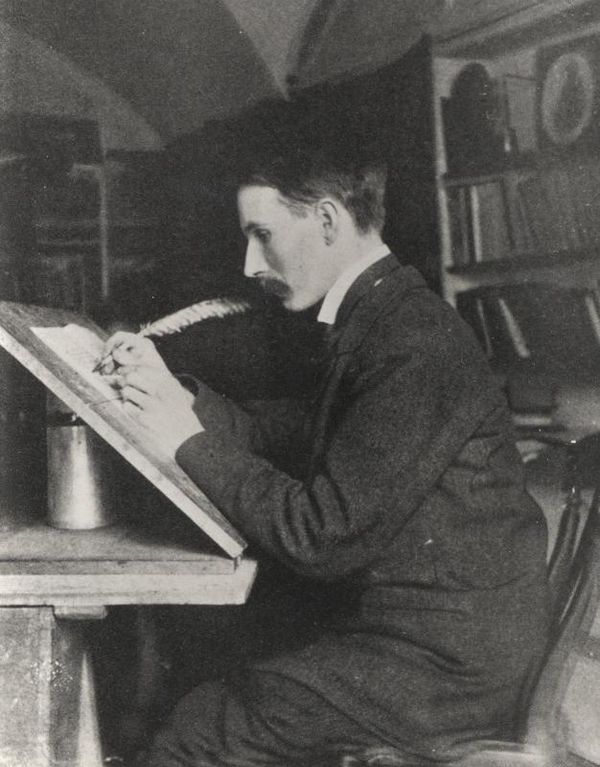

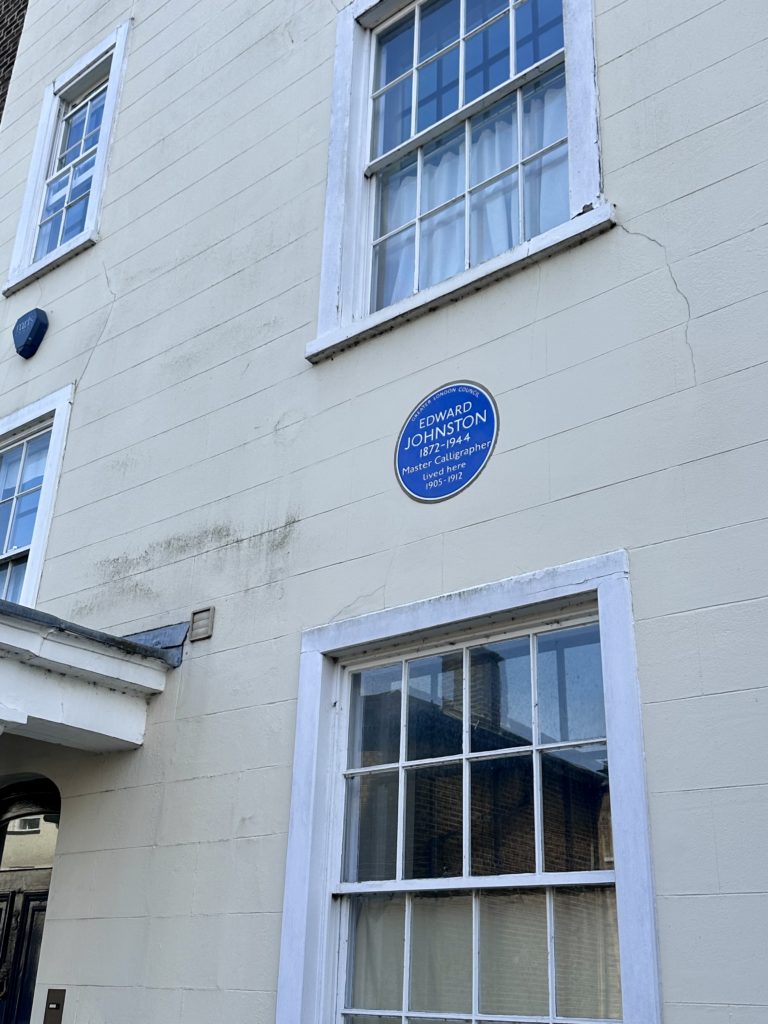

There is some kind of magic at Hammersmith Terrace. The rowhouses were built in mid-1750s, when Hammersmith was largely a rural community west of London. In the late Victorian era it was central to the Arts and Crafts movement. No. 7 was home to T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, an artist and designer who curated a particular interest in printing and typography. He soon decamped for a place a few hundred yards up the river and the home was bought by Emery Walker who had been living a few doors down at No 3. (Just for fun: Before that, No. 3 was home to Edward Johnston, the designer who created the official font and rondel for the London Underground. This is what I’m saying — Hammersmith Terrace has something in the walls).

Emery Walker was married to Mary Grace and they had a daughter Dorothy. By the early 1900s, Hammersmith was no longer a bucolic farmland. It was industrial and sooty. Mary Grace found herself unable to cope with the poor air quality and was rarely at the home with Emery and Dorothy.

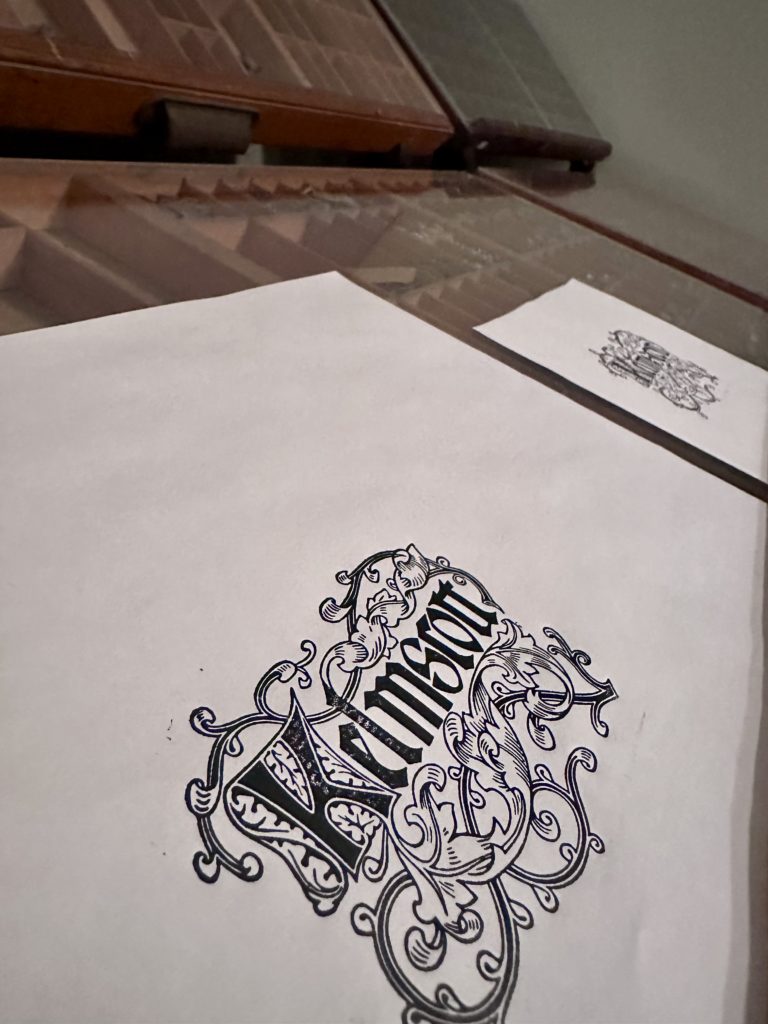

Also just up the river was the home of William and Jane Morris. Kelmscott House was headquarters for the Kelmscott Press, an independent print focused on beauty and romance in the art of typography and illustration. The carriage house and basement of Kelmscott House have a few artefacts from the printing days.

So, back to Emery Walker. In this mix and match melange of talents and interests, Emery Walker found friends and artistic inspiration. He shared the love of medieval manuscripts, pre-Raphaelite sensibility, and the honoring of handmade craftsmanship. He became very close with the Morris family and was gifted many original pieces. The dining room is draped in blue “Bird” pattern tapestry, and papered in Morris & Co. “Willow” wallpaper. Chairs are covered in Morris upholstery and a footstool was embroidery by May Morris. It’s visually a lot to take in, but it works and has a tremendously cosy feel to it.

[By the way, none of the interior photos are mine. Photography is not allowed in the home. The above are from the Emery Walker Trust website. They have many more and a very cool 3D tour online.]

In addition to admiring Morris and Arts & Crafts design, I’m a bit of a nerd for fonts and typography. It turns out, Emery Walker’s House is center stage for one of the biggest font disputes in modern history. Walker was peripherally involved in Morris’s Kelmscott Press. When Morris died in 1896, Walker helped the Press finished printing its remaining projects. It was then disbanded in 1898. T. Cobson-Sanderson saw the need for a similar, artistic independent press and convinced Walker to partner with him in creating Dove’s Press. It was named for the pub next door to Cobdon-Sanderson’s office. Literally next door. As in, they share a wall.

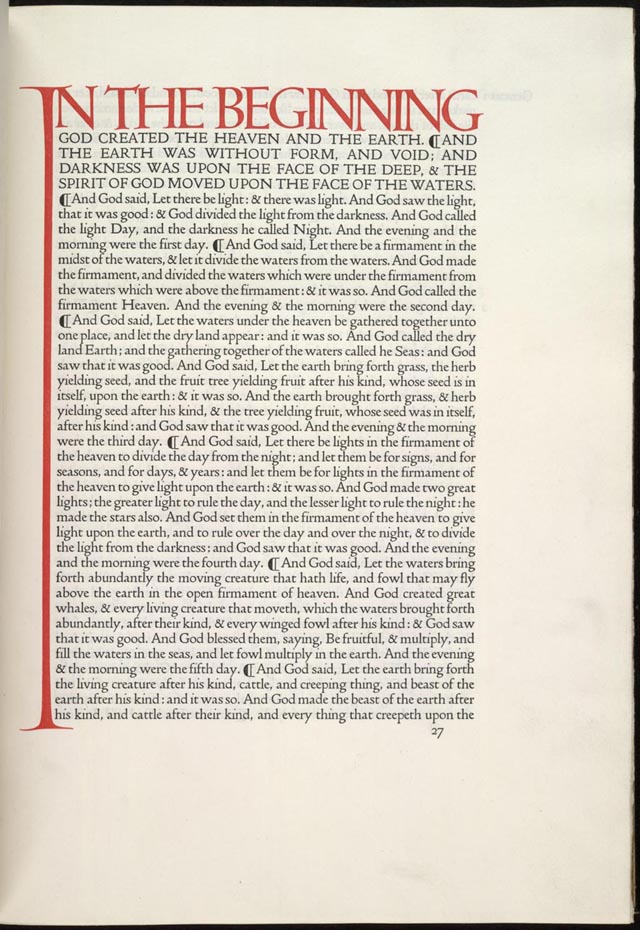

The two designed a new font, that mirrored the style of old manuscripts that they loved, but which was lighter and easier to read on the page. It was drawn by Percy Tiffin and cut by Edward Prince. The typeface was called Doves Type and it was used in the press’s printings, the most famous and beloved being the Doves Press Bible.

Though books were selling and the press was well-respected, the two men eventually found they were not the best of business partners. By 1906, the two agreed to part ways. In 1908, Walker suggested the entire enterprise be shut down and asked for his half of the remaining assets, including his interest in the font. The two wrote one another into their wills as the deeding over rights to the Doves Type upon either’s death. It seemed settled. But by 1913, Cobdon-Sanderson, considerably older than Walker, began to have second thoughts. What if Walker used the font on projects after he’d died? Ones he wouldn’t have approved of? Why should Walker financially benefit from the font?

So, Cobdon-Sanderson took a number midnight walks across Hammersmith Bridge, each time dumping the font into the River Thames. First the matrices and punches, then the type pieces itself. It’s estimated he made more than 150 trips to get rid of the beloved font. For more than 100 years, the font only existed in the printed pieces that survived. Then a font enthusiast got permission to dive and excavate under the bridge, and many Doves Type pieces were recovered.

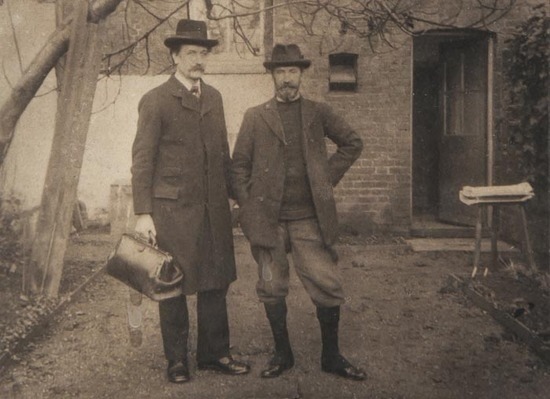

Emery Walker & T. J. Cobden-Sanderson (via Bruta-Bruta) and The Doves Press type recovered from the River Thames (photograph by Sam Armstrong, via Typespec)

A few of the pieces are now on display the Emery Walker House and I was beyond thriller to hold them in my hand for a minute. Following my tour, I walked along the Hammersmith Thames path, past The Dove and over Hammersmith Bridge. I imagined hefting lead type up and over the railing, all the while keeping the house at No. 7 Hammersmith Terrace in view. I wondered about the men that were brought together by elevating an artform and divided by the destruction of it.

John Keats House

A world away from Edwardian design, on the edge of Hampstead Heath, is a lovely, modest house. When it was built in 1815, it was semi-detached. The owner invited John Keats to live in one half, as his boarder, in 1818. When the owner moved to central London, it was rented to Fanny Brawne’s family. Keats and Brawne fell madly in love and became engaged here. Keats also wrote a number of his most well-known works here — “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” and “Ode to a Nightingale” included.

Keats is probably my favorite poet, if forced to choose one. I enjoy the works of a number of the Romantics (though after I heard Byron called Wordsworth Turdsworth I’ll never forgive him). Weirdly, to me Keats feels so out of time, so ephemeral, I never really thought about where he lived or what he did with his days. It didn’t occur to me to seek out his literary grounds the way it has for so many other favorite authors.

The evening I visited, the Keats House they were holding a Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein event, which was how it popped up on my radar at all. With monster-themed mocktails, Gothic bracelet-making in the basement, and university lecturers, my visit was a true joy. Much of the home has changed a great deal since Keats lived in it, and there are only a few museum pieces but that also means the house is much more flexible. Visitors can roam comfortably and it can host events easily. I had a fantastic time exploring the home and gardens, as well as enjoying a scholarly lecture and making a silly bracelet.

When you travel, be sure to seek out these small house museums. I promise the immersion you’ll feel will make a much more lasting impact than a dip into a famous gallery.