Humanity has always had a concurrent fascination and repulsion with the “other.” And since the beginning of cinema, that fascination influenced the screen. The Lumiere Brothers began by sending cameramen around the world to gather footage from far-off places and strange lands. While travelling, they also exhibited the films, or travelogues, they were collecting.

Travelogues featured exotic locales with native cultures for the education and pleasure of the viewer, or at least that was how they were sold. Since the early days of film, the travelogue split, and two separate paths have emerged: A documentary style and a narrative style. Hallmarks of the early travelogues still exist in the guise of this genre, and can be seen in the grand epic of 1962, Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence of Arabia is based on T.E. Lawrence, an Oxford-educated archaeologist, working mostly in the Middle East. He parlayed his expertise into a position with the British Army in Egypt during World War I. While there, he was instrumental in helping Arabian forces battle the invading Ottomans. When he returned to England, he was hailed as a hero.

Lawrence engaged in a number of speaking engagements and lectures, recounting his adventures in Arabia. He also wrote a popular autobiography, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, of his time that became the main source of the film. When he died in a motorcycle accident in 1935, Lawrence took on a legendary status. It is the legend that finds its way onto the screen. The origin of the Lawrence legend began with the early travelogue, and some forty years later, David Lean would solidify that legend with his stunning film, Lawrence of Arabia.

Films in the historical epic genre represent the modern version of an attempt to capture a complicated subject in a condensed form. As a genre, the historic epic makes claims of realism, which are underscored by the fact that real people are characters in the film, the location shooting, and, often, the length. These aspects of the historical epic genre lead the viewer to assume that the film is a fairly accurate account of that particular piece of history. Lawrence of Arabia has become a pocket encyclopedia of the Arab Revolt and T. E. Lawrence’s involvement in it for millions of Western viewers. Yet, the real history was far more complicated and multifaceted.

The historical epic genre also features a distant location, in place or time, or both. This location shows the way of life for the native people – how they live and what their surroundings look and feel like. It boils down complex issues that exist within a culture, people, and places to a few cinematic hours.

The location portrayed in Lawrence of Arabia is precisely the type to be made exotic by the early travelogue. The desert is mystical. The imagination of the viewer brings with it images of Scheherazade and Aladdin, genies, harems, ancient curses, fallen empires, magical and beastly gods, and mysterious people. Tribes of bedu were separated by natural boundaries and fought for control of small pieces of oases in the scorching desert.

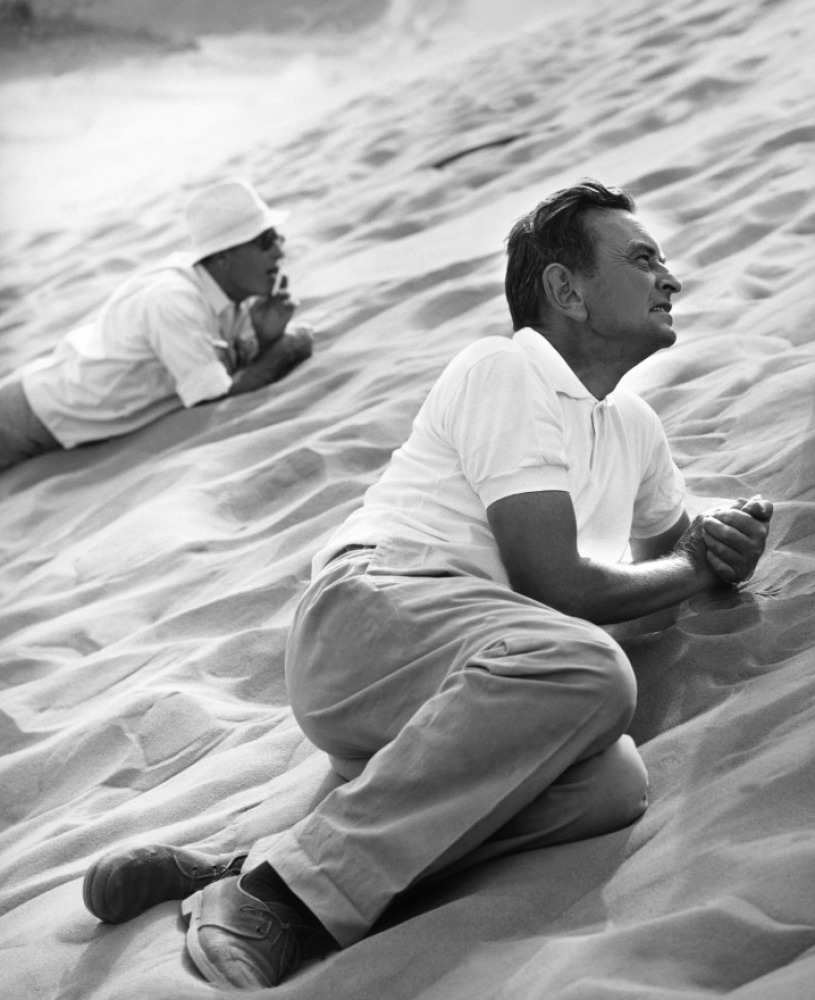

Such desolate landscape was a blank canvas for director David Lean in the making of Lawrence of Arabia. He wrote: “The mirage on the flats is very strong and it is impossible to tell the nature of distant objects. … I can also see how the desert can mean something, little or nothing to various people. I found it a stimulant. … It somehow threw me back on myself and made me very consious [sic] of being alive. There you are. Just you and it. … Everyone is somehow more on their own out there, and perhaps they just have to come face to face with themselves if they come under its spell.”

Little, physically, had changed since Lawrence’s time there (“There are lots of remains of Lawrence’s blowing ups” ). Its ancient austerity influences the feel of the film and Lean was determined that the audience would see the desert as he saw it, and as he thought Lawrence saw it. Some of film history’s most famous shots were created in Lawrence of Arabia. The two minute single-shot entrance of Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif) from mirage to reality is stunningly simple and effective. It requires the audience’s patience and trust, but it has become a classic in the annals of cinema.

Peter O’Toole struggled to get comfortable in the saddle of a camel until he fashioned a pad out of foam he found at a market. The bedu extras gave him the nickname “Father of the Sponge” and copied his creative solution.

“The making of Lawrence of Arabia was practically a military operation, with Lean commander-in-chief…. It took 20 months to film Lawrence of Arabia, during which the cast and crew had to endure the scorching heat of the desert during the day, the freezing cold at night, not to mention sandstorms, plagues of insects, and being cut off from civilisation for weeks at a time.” — “David Lean” by Howard Maxford

Locations included Jordan, Morocco, and Spain, with a crew of more than 200. The filming was so grueling that Peter O’Toole declined to make any more films on location with David Lean (the part of Zhivago went to Omar Sharif instead).

Lawrence of Arabia also features the most famous jump cut in film history, made by the editor Anne V. Coates.

The historical epic includes an attempt to understand or become like the foreign native, but ultimate failure to do so. There is also an innate sense that the foreign culture could be great, if only they would accept certain aspects of the hero’s outlook. Furthermore, the fact that these historical epics highlight real people, real battles and real places, it is all the more convincing to the viewer that what they are seeing is historically accurate.

The narrator-hero acts as a chalcedony to the local culture so the audience will have something to relate to. The hero’s actions comment on the natives and highlight their differences. Often, Lawrence defies the Arab tradition, which has allowed the bedu to live in this harsh climate. But instead of showing disdain, Sherif Ali is impressed. He says of Lawrence: “Truly, for some men nothing is written unless they write it.”

Lawrence of Arabia explores two disappearing cultures at once. Both the English Victorian era and the bedu culture were fading. Lawrence represents the typical disillusionment of the youth thrown into WWI.

The Lost Generation was raised with Victorian ideals in an industrial age. Encouraged to believe in chivalry, at all costs, they were sorely dumbfounded when wave after wave of their sword-rattling cavalry were mowed down by machine gun fire and nerve agents. Lawrence somehow managed to find that place where the ideals of chivalry still survived. He found a place where he would ride into battle, sword raised, and come out victorious. Lawrence of Arabia provides a glimpse into the psyche of this generation, and it portrays a man who felt out of step with his own family and country to find a home, however temporary, in a foreign culture thousands of miles away.

The second vanishing culture to be showcased in Lawrence of Arabia is of course the bedu. Living the same way for centuries, their traditions are hard-earned and stoic. They had as yet to be overexposed to the modern world. Only the biggest ports were modern cities, and so the bedu continued to live a nomadic lifestyle relatively untouched. Lawrence is able to immerse himself in this foreign world so completely that it seems as though the rest of the world has gone away.

Lawrence of Arabia as a historical epic explores not only a distant land, but an extinct time. In the film, and in Lawrence’s memoirs, he mourns the loss of this culture as it becomes infiltrated by modernity, and indeed the influence of foreign forces like the ones he represented (for example, he was infuriated with the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement that was forged without his knowledge).

Six decades after its release, it is increasingly clear that Lawrence of Arabia is an oversimplification of a complex story with rich and varied details, people, and situations. Shot on 70mm (65mm lens with room for the soundtrack), it is one of the last big, onscreen historical epics of its kind. It is a visually stunning piece of art but from a European perspective. Even so, it is a significant cinematic work and offers a point of view regarding England’s relationship with the complicated T.E. Lawrence.

Originally written for DVD Netflix