In the waning days of William IV’s (unlikely) and nearly constantly tempestuous reign, from the Great Reform Bill and a controversial move to install a prime minister, the passage of an act for peaceful ends must have seemed inconsequential. Yet, the parliamentary action to create the London Cemetery Company and provide for dozens of acres of (then) countryside land be set aside for final resting places proved essential to London’s character and the coming Victorian era.

WHEREAS the Cemeteries or Burial Grounds within the Cities of London and Westminster and the immediate Suburbs thereof are of limited Extent, and many of them having been long in use are so occupied and filled with Graves and Vaults as to be altogether insufficient for the increased and increasing Population in the Neighbourhood thereof, and not equal to afford those Facilities for the Interment of Bodies which is necessary and essential to the Convenience of the present and increasing Population … and other Works by this Act authorized to be made, and for that Purpose shall be One Body Corporate, by the Name of “The London Cemetery Company,” …

~ The 1836 Act

To put it bluntly, the graveyards were full. Small neighborhood churches managed tiny plots for their congregants, but as London’s population swelled, these neighborhoods were swallowed up into the stretching city. Civic and spiritual leaders had no place to lay their former followers to rest. City planners had to look beyond the current reaches and find swathes of land that could house the future dead. The London Cemetery Company was formed.

They were charged with creating, landscaping, managing, and maintaining these new, improved, and transitory places fo the good of all Londoners. For the next few years, the London Cemetery Company would open its ‘Magnificent Seven’ burial parks, incorporating dramatic sculptures, winding paths, and natural settings into their plans.

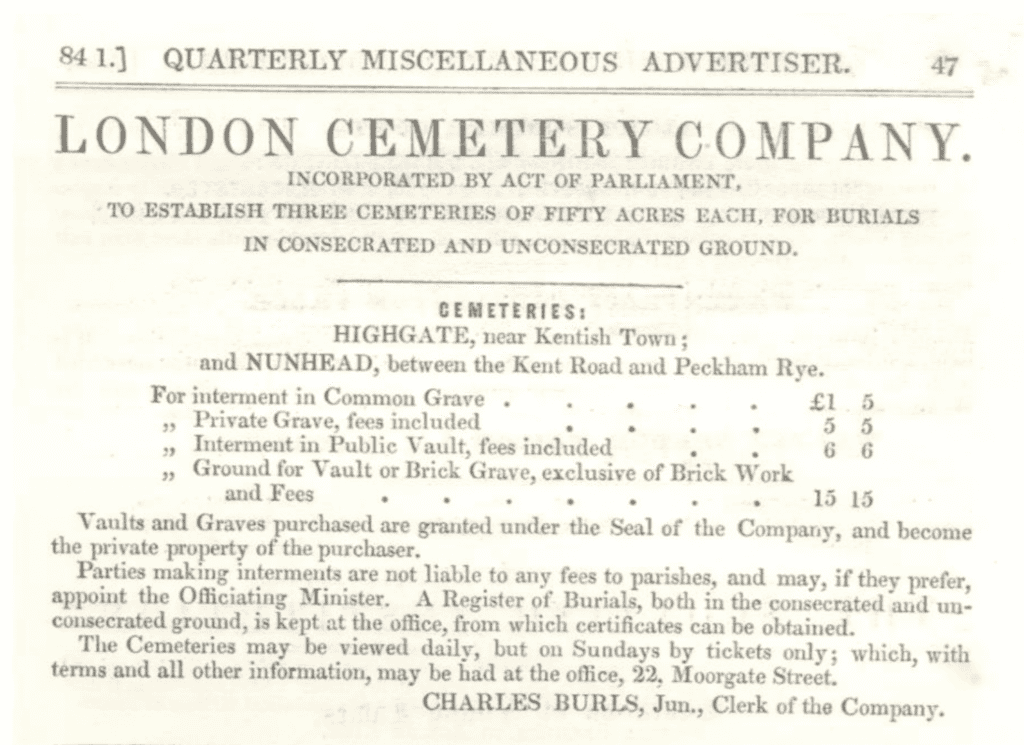

The Company, and its holdings, were privately owned. The shareholders made money by selling plots to families and mourners, so creating a stunning backdrop was in their best interest. A cemetery plot could be considered one’s last, best piece of real estate so an impressive address was in demand.

Highgate Cemetery was finally dedicated and opened in May 1839. Set along a slope overlooking London proper, it was a quiet but imposing reminder of mortality. The wealthy signed up in droves. Within Highgate, purchasers could select from various burial options. Plots were set aside for personal (and massive) mausoleums. A columbarium could house urns. A catacomb carved into the side of the hill was also an option.

In fact, the plots sold so well that the London Cemetery Company purchased another twenty acres across the street and expanded the burial ground in 1856. Today, this “newer” portion is known as Highgate East. Throughout the mid-1800s additional decorative fixtures were added to East and West to attract more clients. It also perfectly coincided with the rise of Victorian mourning culture and the desire for garden-like cemeteries.

Rather than a churchyard filled with graves, this new gravescape would be a place from which the living would be able to derive pleasure, emotional satisfaction, and instruction on how best to live life in harmony with art and nature. ~ Richard Morris, “Burial Grounds,” Macmillan Encyclopedia of Death and Dying.

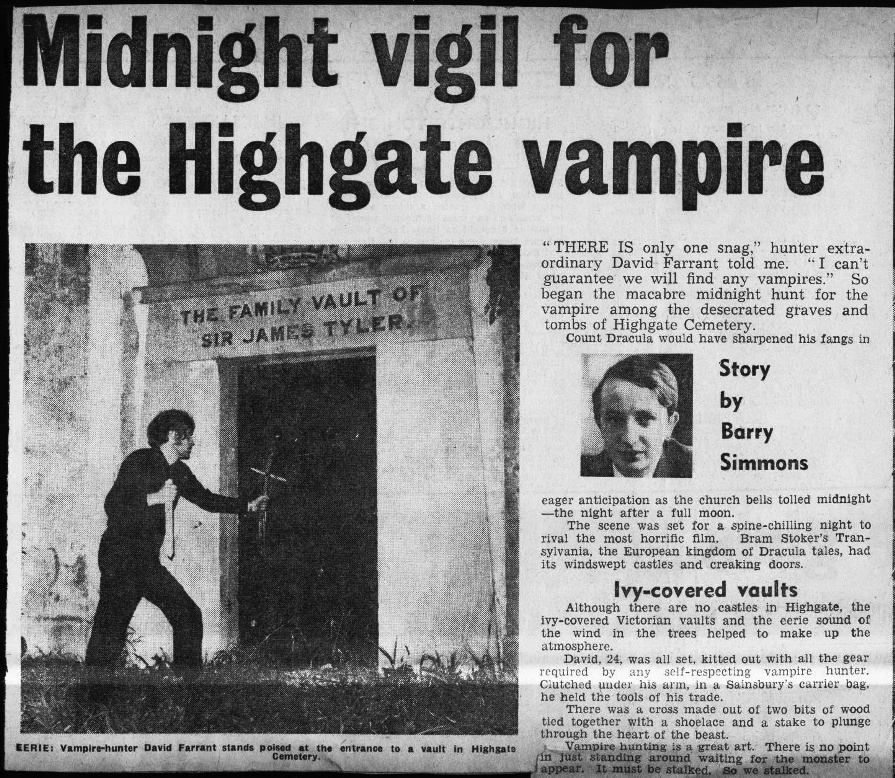

In the 1930s, families began choosing simpler monuments and funeral ceremonies for their loved ones. Burials slowed through the mid 20th century and the London Cemetery Company struggled financially until it finally went bankrupt in the 1970s. In those couple of decades, the maintenance of Highgate declined significantly. Stones went unrepaired and vegetation became overgrown in the extreme. The neglect also led to trespassing and vandalism.

This errant behavior reached a fever pitch in the mid-1970s with the incident of the Highgate Vampire. Spurred on by such cultural touchstones as The Wicker Man, the Satanic Panic, the Enfield poltergeist, and a slog of Hammer horror pictures, local paranormal ‘investigators’ claimed a bloodsucking undead man was victimizing (or at least startling) people around the Highgate Cemetery. The hysteria led to numerous break-ins, damaging ‘ritual cleansings’, and even arrests for desecration.

The bizarre times underlined the London Cemetery Company’s clear inability to properly manage the area. In 1975, the Friends of Highgate Cemetery was formed and became the official keepers of the historic burial ground. Soon after, they began fundraising and continue to act at the stewards of the site as a managed woodland and to preserve and maintain the historical monuments. As a charitable trust, they do not make a profit. Rather all the new burial fees, donations, and admissions go into keeping Highgate Cemetery running.

The terrace catacombs suffered from a a great deal of vandalism as well as neglect in the last days of the London Cemetery Company. “Vampire” hunters and their acolytes broke into the sealed compartments in the search for the undead. The catacombs are now locked and only accessible on a tour or with a employee (Thanks, Nick! You’re the best!).

The top coffin in the next photo is that of Robert Liston, the “fastest knife in the West End.” Liston was a surgeon who could amputate a leg in two and a half minutes, a necessary torture in an era before anesthesia. He was also a pugnacious type who decked Robert Knox for his suspected (later confirmed) underhanded dealings with murderers Burke and Hare. Liston also actively tried to discredit Joseph Lister who advocated for things like clean hands and sterilized surgical instruments. Liston died in 1847; meanwhile Lister’s practices became standard (thankfully).

Highgate East is the final resting place of a number of public figures and eccentrics.

The cemetery should be on any taphophile’s list. In addition to the famous burials, there is some stunning architecture and it is all enveloped by a slightly wild natural setting. One hopes the dedicated Friends of Highgate Cemetery continue to protect and restore this special place.

Get all the details about visiting Highgate Cemetery in north London.